Analysis: England's Rugby World Cup game plan explained

Eddie Jones has referred to his side’s game as a ‘modern’ version of English rugby, an attempt at refreshing an old way of playing.

It is certainly true that they adhere to a game of past ages – the one constant with their game is a commitment to territorial advancement. They simply do not value possession anywhere near as much as territory, using the kicking game to trade the ball for ground upfield wherever possible.

It can be said that for the most part, they do not want the ball.

Whilst the addition of attack coach Scott Wisemantel and a host of new players has sharpened up aspects of their starter plays, the interplay between the forwards and backs is a long way off the level of Ireland or New Zealand. They are not built to hold the ball for long periods of play and the detail in their shape is haphazard at times.

However, what they make up for a lack of creativity, flair and spellbinding play is with bruising defence, punishing physicality, and dominant set-piece fuelled by the territorial kicking of their halves.

On the back of the boot of Youngs and Farrell, England builds the platform to unleash a ferocious defence and continually make the opposition feel like they are going backward – usually because they are.

It sounds simple enough but this is exactly how they do it and what they will do to try to win the Rugby World Cup.

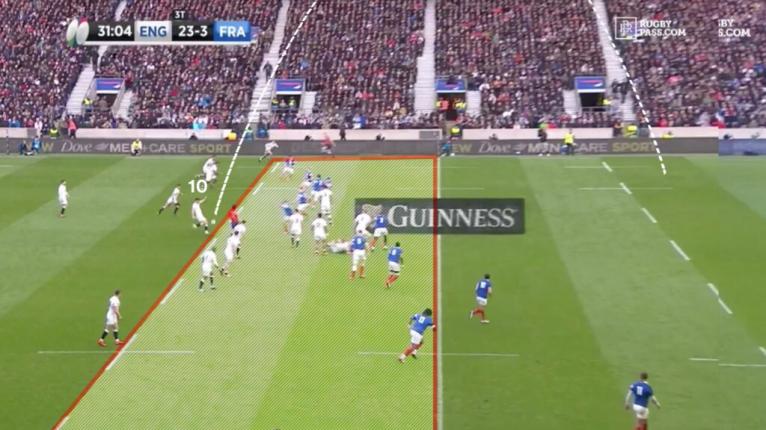

England’s kicking zones

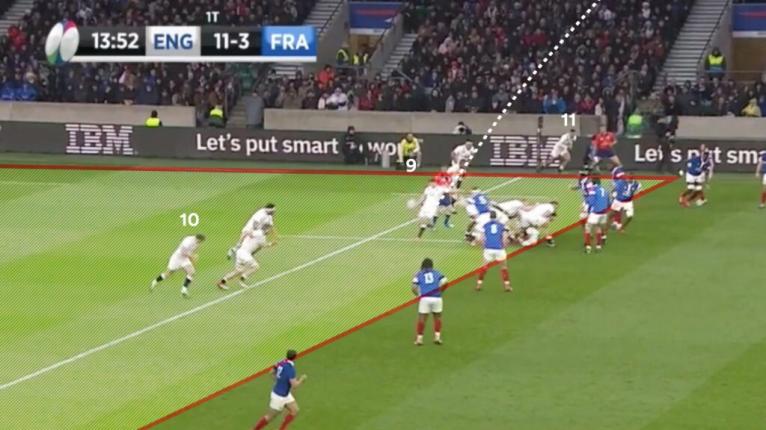

England’s game is constructed around three key kicking zones, the first being the exit zone – inside or just outside the 22m.

Halfback Ben Youngs (9) will handle almost every exit, the most important zone to execute kicks. There is a no-nonsense approach to it, re-positioning the ruck if required but never playing a phase more than required.

Inside the safety of the 22 he can find touch, if not, a contestable ball will be launched.

The ideal landing spot is inside the 5m channel against the sideline between the 40m and halfway, where it can be contested or the recipient can be put over the sideline. Youngs has the ability to do this on a frequent basis.

He can overcook it at times but when Youngs kicks well, it goes a long way towards an England victory, with many possessions re-gathered around midfield setting up the next kick. Flyfhalf Owen Farrell (10) is often part of the kick-chase unit, not in the pocket as a kicking option, even at times getting up for the contest.

This is a quite unique use of the flyhalf in a non-traditional way. Farrell, who is known for his aggressive contact, can get involved in the kick-return contact instead of being tasked with the responsibility of clearing.

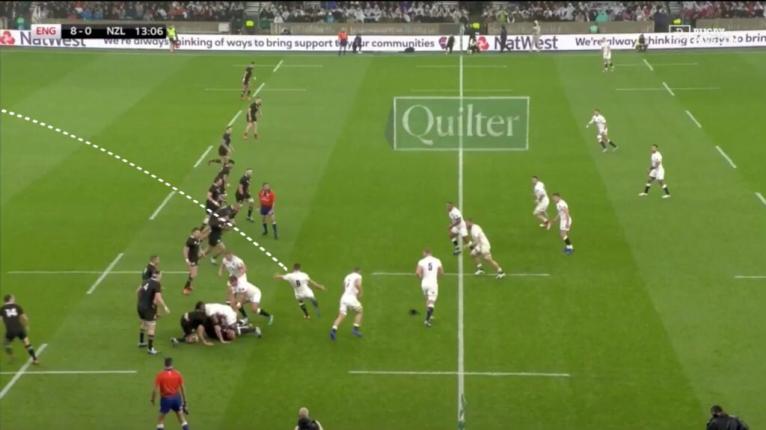

If England are able to regain possession from Youngs’ kick, often they will look to drive another kick downfield targeting the depleted backfield instead of using the turnover opportunity to attack wide.

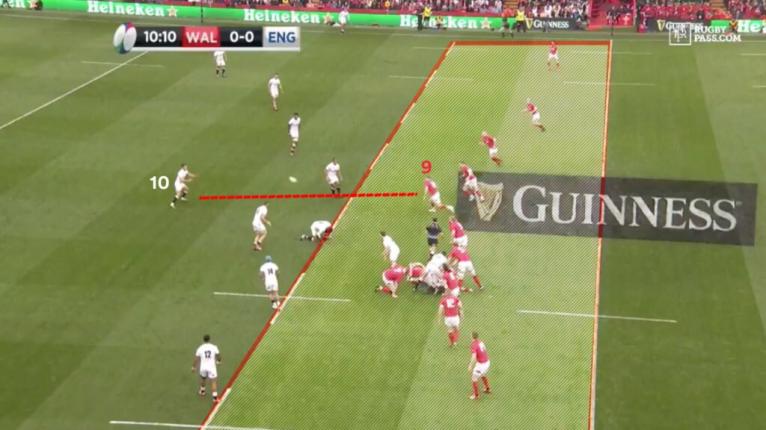

Against Wales, the ball bounces back directly to Ben Youngs who uses a ‘topspinner’ to kick it end-over-end over the touchline deep into Wales’ territory.

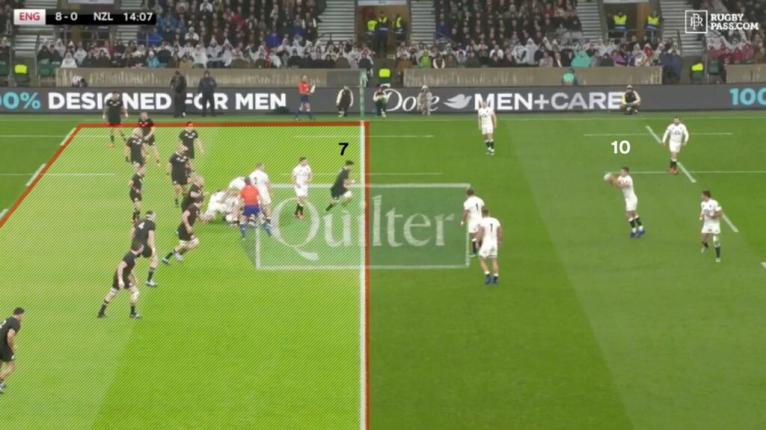

Again, against the All Blacks after winning a kick contest inside their half, Youngs gets a quick recycle and forces them back deep into their own 22 with a tight angle to clear from.

Again, against the All Blacks after winning a kick contest inside their half, Youngs gets a quick recycle and forces them back deep into their own 22 with a tight angle to clear from.

This results in huge ‘piggyback’ territorial shifts in a 15-20 second-time span, often flipping from their own pressure exit situation to the exact opposite with back-to-back kicks but comes at the expense of attacking off turnover ball.

This results in huge ‘piggyback’ territorial shifts in a 15-20 second-time span, often flipping from their own pressure exit situation to the exact opposite with back-to-back kicks but comes at the expense of attacking off turnover ball.

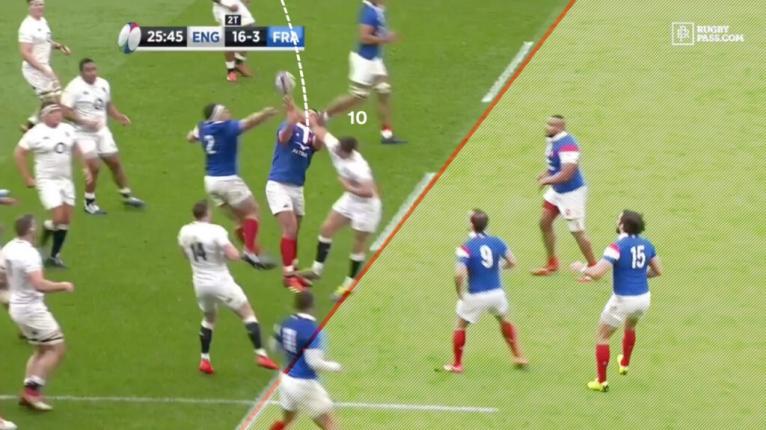

The next kick zone is between each of the 40m lines on either side of halfway.

On this side of halfway, you will often see England send up another contestable kick. It is generally a bomb from Farrell dropping back into the pocket but could at times be another box kick by Youngs.

Despite the relative safety this area of the field offers, the number of phases they play in this area before kicking is low, ranging between 2-5 on average. A few carries or one wide shift may occur before Farrell or Youngs decides to send it to the air.

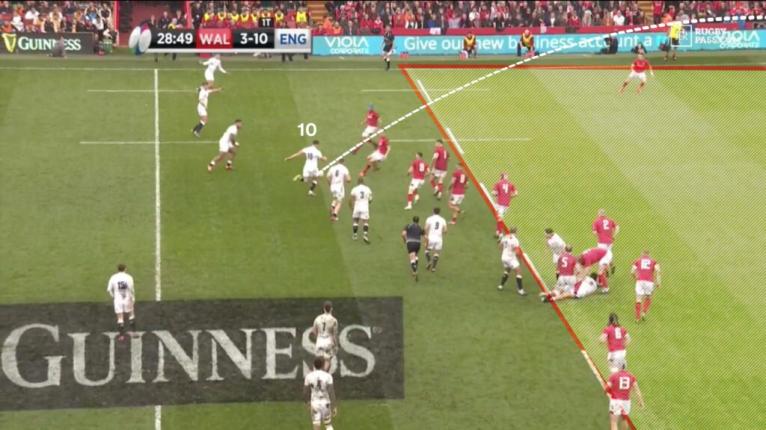

The distinct lack of structure is visible in the shot above after a few phases, with no other planned option but for Farrell’s kick. Even if they wanted to play running rugby, they aren’t in a position to do so.

Farrell’s bombs enable England another contestable ball, this time encroaching into the opposition half where points could be on offer should they regather.

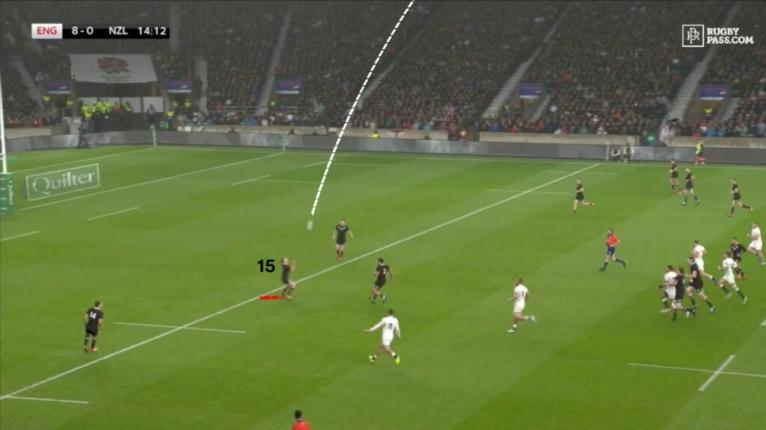

The middle third is where Farrell’s kicking game really comes to the forefront, and it has been this area of the field where England have been vulnerable.

Gareth Davies (9) spies Farrell in the pocket and rushes off the line to pressure the kick. He moves Farrell off his spot and with a lack of any other bail-out passing options, Farrell still attempts the kick and is charged.

This is dangerous for England because this kick occurs like clockwork after the play breaks down, becoming predictable. Farrell often has a slow wind-up and at the same time is usually unprotected without players in front of him. It would be possible in this area of the field to put a ‘spy’ on Farrell and blitz him every time.

Players like Faf de Klerk and Ardie Savea who can get off the line quick would be a major threat to England’s kicking plan. One charged kick recovered could be a game-changing 7 points.

Between halfway and the opposition 40m, a continuation of the same strategy ensues. The bombs and box kicks are launched to land a bit further downfield, inches outside the safety of the 22.

Farrell and Youngs can do this with remarkable accuracy, forcing the retreating team to recover and secure the ruck in a position where a turnover would be costly.

Farrell and Youngs can do this with remarkable accuracy, forcing the retreating team to recover and secure the ruck in a position where a turnover would be costly.

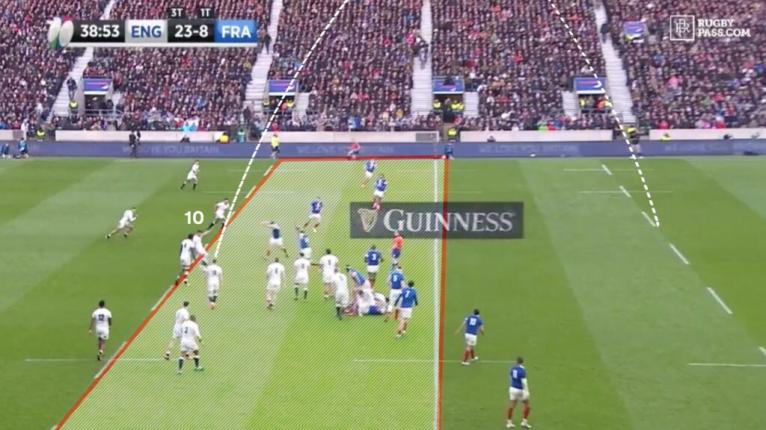

The final kick zone is when England finally have possession inside or around the opposition 40m line as they start to press into deeper into opposition territory. Their play becomes more expansive, reaching the edges with more frequency.

However, if England start losing gain line or can’t open up the opposition, they complete another kick plugging the corners, attempting to force a 5m lineout or a very tight clearing kick.

At times even though they may have the ball pressing into the opposition 22 they will still kick into corner to force the opposition to exit, which is why often the outside backs like Jonny May and Jack Nowell or Henry Slade and Elliot Daly will grubber through.

At times even though they may have the ball pressing into the opposition 22 they will still kick into corner to force the opposition to exit, which is why often the outside backs like Jonny May and Jack Nowell or Henry Slade and Elliot Daly will grubber through.

Why do they kick away so much ball when already deep on attack?

It’s because England really want one specific situation to attack from, it is the one gun where they have all their ammunition loaded, an attacking lineout anywhere from 15-30m out with which they can run their set plays.

Once the opposition clears their lines they will usually receive their desired lineout platform.

They have become increasingly prolific from scoring off this situation using ‘slow-burning’ switch plays after strong first-phase carries from Tuilagi or Vunipola and a few phases of hammering the line around the corner. Against both the All Blacks and Ireland they scored in the first few minutes using these type of switch plays.

However, the number of times they receive these opportunities to craft tries is going to vary. It might only occur two or three times a half if that. If you are going to kick away the ball in every third of the field, patience is required. You must wait to win the ball back through your defence or opposition error, kick and wait again to advance to the next zone.

When you also consider that they will also nearly always take the three points on offer when receiving a penalty in range, England’s laborious grind of taking territorial chunks down the field becomes a game of aerial ping-pong with little actual running rugby.

By the end of the 2018 Six Nations, a tired England outfit was no longer winning with the frequency of the first two years under Eddie Jones. 12 months later, they found a way to rejuvenate the side.

A dominant defence feeds into a ‘winning-territory-at-all-costs’ strategy as you frequently giving the ball away. If you can’t hold or take it back then it becomes futile. England’s defence needed an upgrade.

The emergence of Tom Curry and Sam Underhill as twin world-class flankers was central to this, as was the addition of underrated Mark Wilson. The aging Robshaw and Haskell were replaced when Jones took a punt on Curry on the mid-year tour of South Africa.

The 20-year-old Curry has since emerged as one of the breakout stars of international rugby and brings a relentless motor, bruising defence and turnover ability to England’s already formidable pack.

England’s backrow became faster, more agile but with newfound aggression. Dylan Hartley was also left on the outer as part of Jones’ plan to kickstart his pack.

It was part of the juice required to reboot England’s system, along with a healthy Billy Vunipola. They emerged in the 2019 Six Nations with a ferocious defence able to dominate the gain line again, as well as take the ball off the opposition frequently.

One plan fits all

England has used the same game plan against South Africa, New Zealand, Australia and every opponent in the Six Nations. It worked spectacularly against France but lead to effective stalemates against Wales, Springboks and the All Blacks with each result decided by a few points or less.

If England captures their second World Cup with this strategy, it will prove that rugby can still be won playing with traditional old school strategies although it won’t be a celebration of innovation and running rugby. They will, however, have to a great defence and that will be something to marvel at.

Former England fullback Ben Foden documentary: