They say rugby is a young person’s game. Take a moment to ponder the lifetime of a referee. The average age for the panel of referees officiating at the 2025 Rugby Championship is only 36 years old. In the prime of life, rugby is a full-time occupation for those who officiate and play the game alike.

As one of the cadré of youthful referees in the burgeoning English Premiership, Tom Foley is one of those pioneers who have been hacking a new path through the professional jungle. He has been a full-time referee ever since 2014, having officiated over 100 games in the Prem and featuring regularly as a TMO in international games.

“There is a perception you just turn up on a Saturday, then spend the rest of the week watching TV,” he told BBC Sport in 2023. In fact, a referee’s weekly schedule is as full as that of any player or coach. There are performance reviews early in the week, followed by interval training and weights – “Tuesdays are the killer” – and team previews as Saturday draws nearer. Just like the players out on the field, referees work with familiar faces throughout the season in three-man pods or crews.

If rugby is a business, the players are its merchandise and the referees are the salespeople who dress it for the shop window. They are rugby’s essential connective tissue. They interpret the law and communicate it to the wider rugby public. As Foley explains: “We build a picture of the game before feeding back to the rest of the group. If I have done something and the group [of referees] agree that is how we want to referee going forward, we will then make sure we do it next week. There is a genuine feeling that we can make the whole officiating appear better if we are all working together.”

Six months after that interview appeared, Foley was the TMO for the Rugby World Cup final between South Africa and New Zealand in Paris. What should have been one of the proudest moments of his career was stained by the abuse he received after the event. Foley even had to contact the school his children attended because of emails containing malicious threats to hunt him down and ill-wishers hoping he would die in a car crash.

Two of the biggest matches at the weekend, the World Cup final at Twickenham between England and Canada, and the first game in the Bledisloe Cup double-header between Australia and New Zealand at Eden Park, illustrated the issues a modern referee faces, particularly in the ongoing crux areas at scrum and breakdown.

There are no fewer than 29 possible penalties and 20 potential free-kick offences in Section 19 of the lawbook, which governs the scrum. That is a lot of information for the referee to process in a set-piece which lasts around 30 seconds from set-up to finish.

England were the undisputed queens of the scrum at the 2025 World Cup and they proved the point emphatically against Canada, winning five penalties from the set-piece and another turnover from free-kick. Over the entire tournament, they won a massive 27 penalties while conceding only four and that stat as much as any other reaped the ultimate reward at the old cabbage patch.

One of the magical micro-stories underpinning Red Rose success was the healthy rivalry between Maud Muir and Sarah Bern at tight-head prop. One plays for Gloucester-Hartpury, the other represents Bristol. One is a female version of Frans Malherbe and an exceptional scrummager, the other is modelled on Tadhg Furlong and a superb all-rounder. As Muir herself observed: “Sarah Bern is a big role model for me. We obviously play the same position, but I think she was probably the first of a new era of props.

“You see the things that she does in open play, it’s crazy. She runs through people, her footwork, her change of direction is actually mad. I could only dream of having that.

“I probably would truck it up the middle a bit more, go into contact, but it’s a good mix… it’s kind of a good dynamic to have healthy competition.”

When head coach John Mitchell decided to start Muir ahead of Bern, it was a sign he had come down on the side of a tough-minded, tournament-oriented game-plan based principally upon forward power and defensive excellence. England’s scrummaging at the World Cup was a class ahead of everyone else, and as such it fully exploited the grey areas of that 49-rule lawbook in the final.

Hollie Davidson has a clear remit to avoid awarding penalties and produce as much usable ball as possible from the set-piece, but the final demonstrated how a referee can be ‘persuaded by repetition’. Davidson made three different decisions on each occasion when England replicated the same scrum.

The Red Roses want to shift across the face of the Canadian front-row from left to right, and Muir’s key objective is to move her right foot outside the left foot of her opponent, McKinley Hunt. In all three cases, the scrum lurches sideways before it goes forwards, and the differences are marginal. Davidson allows play to continue in the first instance, calls for a reset in the second, and awards England a penalty at the third. According to law 19.19, players may push provided they do so straight and parallel to the ground. It would be harsh indeed to punish England for their obvious physical dominance, but the means to achieve it are technically ambiguous.

Something similar happened at the beginning of the game between South Africa and Argentina in Durban.

Australian referee Angus Gardner is one of the best and most experienced officials in the world. There is a reset at the first scrum after he calls ‘use it!’ just as Thomas Du Toit heaves forward on the Springbok tight-head side and a knee touches the turf. At the second, there is no hint of South African dominance and the scrum collapses straight down. It is Du Toit’s knee which scrapes the grass first but the penalty is awarded to the myrtle-and-green. Refereeing perception is still king at scrum time, and coaches will do everything in their power to influence it.

The breakdown already features 31 potential penalty sanctions and three other free-kick offences. Italian referee Andrea Piardi, who adjudged Jac Morgan’s cleanout to be legal in the lead-up to the British and Irish Lions’ series-winning try in Melbourne, took charge of Saturday’s Bledisloe showdown.

Piardi’s decision drew the ire of Stan Sport’s Morgan Turinui back in July, and the ex-Wallaby centre was equally critical of Piardi’s performance at Eden Park: “The Wallabies [have to] be more accurate and not allow a referee that’s not up to this occasion, that’s been appointed by World Rugby in error, to take them out of the game.”

Mark Twain once said, “A lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is still putting on its shoes”, and that is especially true in the social media era. Let’s peel the onion a little more than Turinui was willing, or able, to do.

- The final penalty total was 15-10 in New Zealand’s favour, but up until the 45th minute nine of the 13 penalties had been awarded to the Wallabies. For the final 35 minutes that trend was reversed, with the All Blacks being awarded 10 of the last 11 penalties.

- The Wallabies have won the penalty count in all three of their games involving New Zealand referees [plus 11 cumulatively] but are sitting at minus 12 in the past two matches managed by European-based officials. The number of penalties conceded at the ruck has risen with each successive game, in the following progression 1-3-6-7-8.

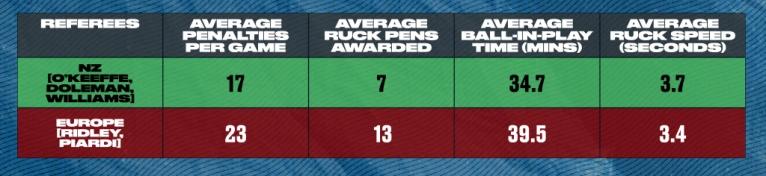

- A table of refereeing tendencies at the breakdown in those five games offers some fascinating reveals:

The two Europe-based referees [Piardi and Christophe Ridley] have awarded more penalties and a higher proportion of them have been at the ruck – 57% as against 41% awarded by the Kiwi officials. At the same time, they have produced two games with almost five minutes more ball-in-play time, with a notable increase in the speed of ruck delivery.

The Wallabies need to confront a scenario where they have conceded more penalties at the ruck in every match, and they need to adjust to European referees, who are stricter at the breakdown and want to deliver quicker ball from it. As Wallaby head coach Joe Schmidt pointed out after the game, it is a failure of adaptation by his charges: “I do think that we’ve just got to be better at adapting to how the referee is refereeing and if you don’t do that, then you pay the price as we did today.”

One of the comparisons highlighted on Stan Sport involved two pilfers won by first Ardie Savea for the All Blacks, then Tom Hooper for the Wallabies.

Law 14.5 [d] requires the tackler to ‘allow the tackled player to release or play the ball.’ In modern refereeing praxis, that means showing an obvious release before diving back in for the steal. Savea raises his arms to erase all doubt, Hooper does not.

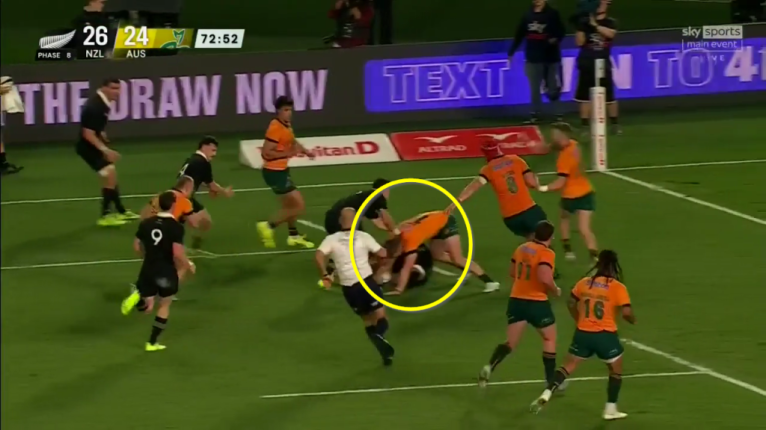

The final straw was Harry Potter’s yellow card in 73rd minute.

Potter is clearly propping himself up on his left hand before scooping the ball back, and Piardi is in ideal position to see the offence. There is no fairytale turnover at the end of the refereeing rainbow.

In the movie Shadowlands, the CS Lewis character and author of The Chronicles of Narnia proclaims “The magic never ends” to young Douglas Gresham. “Well, sue him if it does,” comes the answer from his down-to-earth single mother Joy. The Wallabies could do with a dose of that salty, matter-of-fact realism right now. You cannot always be on the right end of the penalty count as they were at Ellis Park against the mighty Springboks.

Adapting to all refereeing styles and cultures is part of the growing pains of all promising teams who will be greater in future than they are right now. Joe Schmidt’s Wallabies and Kevin Rouet’s Canadian women fall into that category. The referee needs to be massaged. Persuaded to believe what you believe. The best lies always contain a grain of truth.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free