A day after the All Blacks took an enormous amount of pressure off themselves and new head coach Ian Foster by convincingly beating the Wallabies at Eden Park, Foster made a significant reference to Australia, who had held his side to a draw in Wellington a week earlier.

“They’ve got a new coach and the last three new coaches they had beat us in their first game,” Foster said. “If you go back and look at [Robbie] Deans and [Michael] Cheika and [Ewen] McKenzie, they won their first games against us so clearly it’s a team that responds to a bit of change.”

The All Blacks, though? Not so much.

For all of the All Blacks’ dominance over the past decade or so, the most striking of which is their counter-attacking wizardry, a style of play which feeds off chaos, New Zealand are at their most consistent when their combinations are likewise settled.

Wallabies head coach Dave Rennie, in his first test, got good value from selecting James O’Connor at first-five and debutants Hunter Paisami, Harry Wilson and Filipo Daugunu in the starting XV in Wellington, whereas the All Blacks looked far better at Eden Park with Jack Goodhue and Anton Lienert-Brown back in the midfield after Rieko Ioane’s surprise selection at centre the week before, although an improved performance from the pack and Beauden Barrett’s return in Auckland also helped significantly.

O’Connor’s unavailability due to injury for the Bledisloe III Sydney test, combined with a defensive and tactical performance from the All Blacks which swept the Wallabies off ANZ Stadium in a record-breaking 43-5 win, means Rennie’s rebuilding job appears bigger than many had expected after his relative success in Wellington.

But in Sydney the All Blacks appeared far more comfortable than in their previous two tests in New Zealand because this outfit don’t like change for the sake of it.

They much prefer certainty – it’s why the Thursday afternoon training slot before a Saturday test is called a “clarity” session and why their weekly training structure hasn’t changed much in well over a decade.

When New Zealand hit on a winning formula they tend to stick with it and when nearly all Kiwis can recite the All Blacks from 15 to one by rote, that’s when the national team tend to be at their most dangerous; for example when Walter Little and Frank Bunce were immoveable objects in the midfield in the 90s, or Ma’a Nonu and Conrad Smith similarly over a record-breaking 62 tests and two successful World Cups together, or when the Jerome Kaino, Kieran Read, Richie McCaw triumvirate was untouchable.

In fact, Smith was still fuming days after being replaced by Sonny Bill Williams during halftime of the World Cup final victory over Australia at Twickenham in 2015.

For all of the All Blacks’ dominance over the past decade or so, the most striking of which is their counter-attacking wizardry, a style of play which feeds off chaos, New Zealand are at their most consistent when their combinations are likewise settled.

One of Williams’ first acts was to provide the offload from halfway for Nonu’s remarkable try, but so certain was Smith of his place in the team – in his final match for the All Blacks – that he was utterly dismayed at being told he wouldn’t run out for the second half.

That traditionally cautious selection logic is why the sight of fullback Leon MacDonald in the All Blacks midfield in the 2003 RWC semi-final defeat to Australia was so hard to fathom, and in hindsight, Scott Barrett’s selection ahead of Sam Cane on the side of the scrum in Yokohama for the RWC defeat at the same stage to England last year was similarly odd.

Most selections have been as predictable as autumn following summer, although helping that logic and on-field success has been a continuous stream of talent.

For example, the progression from Mils Muliaina at fullback to Israel Dagg to Ben Smith made perfect sense. If not Brad Thorn and Sam Whitelock in the second row, then Whitelock and Brodie Retallick.

Mo’unga’s emergence as a world-class No 10 following the shifting to fullback of another, Beauden Barrett, who replaced Dan Carter, speaks for itself and you only have to look at Rennie’s issues in finding players capable of making the leap to test rugby in Australia to realise it’s not as straightforward as the All Blacks make it look.

For the All Blacks, there were never going to be any selection surprises at the 2011 World Cup (other than those forced by injury which is why Aaron Cruden and Stephen Donald found themselves in the squad), or at the tournament four years later, although Graham Henry and Steve Hansen, the respective head coaches, were assisted by both form and greatness in terms of their personnel.

Of all the combinations that provided the bedrock upon which much of the All Blacks attack was built over their hugely successful period between 2010 and 2015 it was the Nonu/Smith alliance that was the most significant.

They were the power couple that had everything – power and surprising pace from Nonu and the tactical genius of Smith, who, with the ball in hand, was often slipperier than an eel in a thunderstorm. And one of the most significant things they had was time together.

Once that pair left the scene after the 2015 World Cup final the All Blacks went primarily with Ryan Crotty and Sonny Bill Williams (13 test starts) and Crotty and Lienert-Brown (10 test starts).

Both Crotty, an excellent defender with good feet on attack, and Williams, capable of the extraordinary, formed a nice little and large balance but were prone to injury and therefore didn’t play as much as they would have liked.

Rather than solidity and certainty, between 2016 and the end of last year, the midfield was characterised by inconsistency and uncertainty, which made the selection of Ioane alongside Goodhue for Bledisloe I in Wellington such a surprise.

Rather than quickly cement an obvious partnership in waiting, one which could last until at least the 2023 World Cup, the selectors went for a converted wing in Ioane who played well in the Blues midfield this year but who has been exposed there defensively in the past and who was an unknown quantity there as a test starter. That knowledge-gap was highlighted in the second half on the way to Marika Koroibete’s try.

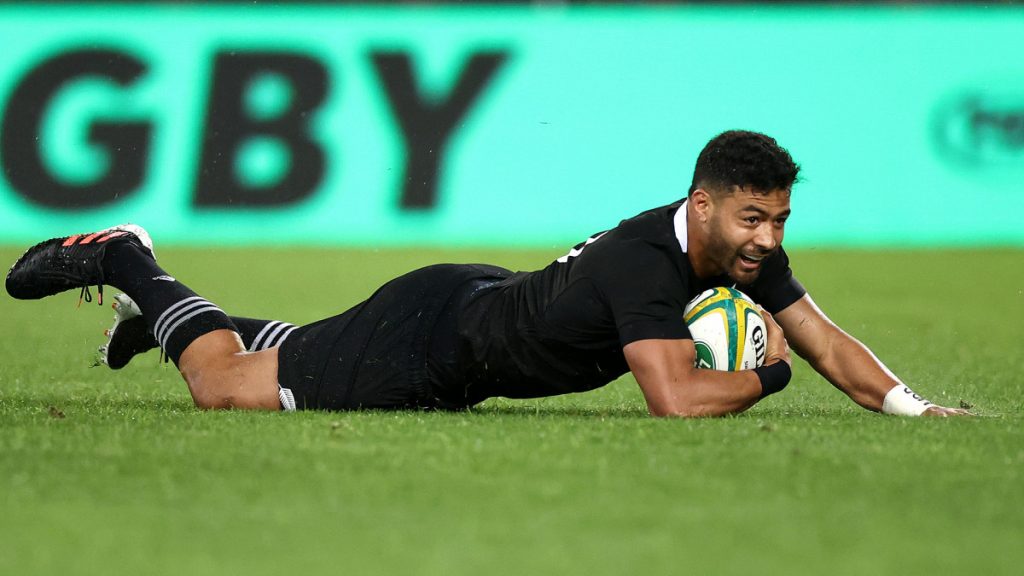

The All Blacks’ stunning 43-5 victory in Bledisloe III was built on a defensive effort which rocked the Wallabies from the first whistle and destroyed the confidence of Noah Lolesio, on debut at first-five in O’Connor’s absence.

But it was also a testament to their growing understanding in terms of their combinations. Mo’unga and Beauden Barrett led their team on a merry dance because their attacking platform was impeccable; provided by a dominant set piece and a midfield combination of Goodhue and Lienert-Brown which now looks untouchable for the big tests.

This is not to say that selection boldness doesn’t sometimes pay dividends for the All Blacks – Steve Hansen’s roll of the dice in picking the untested Sevu Reece and only slightly more experienced George Bridge for the Bledisloe Cup test at Eden Park last year after the calamity in Perth seven days earlier was an immediate, stunning success.

But it was also a testament to their growing understanding in terms of their combinations. Mo’unga and Beauden Barrett led their team on a merry dance because their attacking platform was impeccable; provided by a dominant set piece and a midfield combination of Goodhue and Lienert-Brown which now looks untouchable for the big tests.

It’s just that some combinations should not be tinkered with when total understanding between the individuals involved is implicit in its success or failure.

Like the combination between Mo’unga and Beauden Barrett which is becoming one of the most exciting attacking forces in the world, Goodhue and Lienert-Brown look far better when they are on the field together.

Foster faces a juggling act for the rest of the Tri Nations, but a pecking order has been established.

“I know people are interested in players getting game time and all of that, and sometimes that happens and sometimes it doesn’t, but what’s important in an international environment and our environment particularly – for us – is that players have to be learning during every week they’re here, so that’s our focus,” Foster said in Sydney before his side crushed the Wallabies.

“And clearly it would be nice to reward everyone with game time, but you reward those who deserve it and there are often people who miss out on that carrot at the end of it. We’d love to be able to play everyone – we’ll see how it unfolds over the next few weeks.”

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free