Even before the world was turned upside down by Covid-19, it was difficult enough to get a handle on the lay of the land in men’s test rugby.

In the first place, the dearth of fixtures — compared, at least, to the club game — means that there are fewer meaningful data points which we can analyse and base our thoughts on.

The fact that many games are incredibly tightly contested complicates matters further – since the start of 2016, 37 per cent of men’s test matches between Tier-1 nations have been decided by seven or fewer points.

As illustrated by the first test between the British and Irish Lions and Springboks in Cape Town — a match in which the visitors’ five-point winning margin could easily have been overturned had the officials adjudicated a number of critical incidents differently — the outcome of a given fixture can be contingent on a number of different factors over which neither team has any real control.

However, the emotional intensity that so many observers bring to international rugby — and which gives the sport so much meaning — can make this difficult to acknowledge.

After willing Maro Itoje (or Eben Etzebeth) to lead your team to victory for 80 minutes, it’s not always easy to sit back and consider that maybe such a brief period of time is insufficient to accurately assess the relative standing of the two teams in the arena.

More robust patterns do start to emerge once you get a larger sample of fixtures to look at — but, even then, the rug can be pulled out from underneath you. The passing of long stretches between some international windows means that a test team that emerges from the tunnel in one game may have little in common with its last iteration — other than the colour of its jersey.

And, of course, coronavirus has made all of this even more difficult.

The absence of crowds from many European tests, for instance, will have skewed the competitive balance of those games considerably. While there were only 19 away wins in 60 men’s Six Nations fixtures between 2016 and 2019, the 2021 edition of the tournament — played in front of completely empty stadiums — saw the visiting team win eight matches out of 15.

The lack of meaningful crossover fixtures between the north and south has also made gauging just how the two hemispheres stack up much harder than usual. Even in the series that have gone ahead, both Argentina’s and Australia’s wins this July should be caveated by the respective squads Wales and France were able to assemble.

It is worth stopping for a moment and emphasising just how undercooked Argentina, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa are at this point in the cycle by historical standards.

When the top teams from each side of the equator do eventually go head to head, the obliteration of the Sanzaar nations’ conventional calendar of fixtures — and its knock-on effect on each team’s ability to develop their game and build cohesion — is another factor that will have to be borne in mind.

It is worth stopping for a moment and emphasising just how undercooked Argentina, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa are at this point in the cycle by historical standards.

Between the end of the 2019 World Cup and the beginning of August 2021, the Rugby Championship teams will have played 6.5 tests each on average.

At the equivalent point in the last World Cup cycle — 1 August 2017 — those four countries had played 15.8 internationals each.

In contrast, the Six Nations sides have been able to put more effective contingencies in place to deal with the disruption of the pandemic: teams have averaged 15.5 test matches each at the 19-month mark of the 2023 cycle, compared to 18.5 at the equivalent point four years earlier.

With regard to the All Blacks, we likely know even less than we usually would after a run of nine games, given that this July’s series consisted of three tests against Tier-2 opposition.

These fixtures against traditionally weaker nations are often dismissed as irrelevant and useless — but, in our current circumstances, if we want to understand how Ian Foster’s side is tracking we can’t afford to discard them.

Given that, it’s worth thinking carefully about the best away to analyse New Zealand’s comfortable wins over Tonga and Fiji.

Looking at their margin of victory isn’t all that instructive — although it is worth noting that the All Blacks continued their tendency of beating Tier-2 sides by much larger margins than those managed by the other top nations.

Vern Cotter’s Fiji lost their two-test series in Aotearoa by an average scoreline of 18 points to 58.5. For context, their average scoreline against Tier-1 sides between 2016 and 2019 was 18.4 to 31.4.

Identifying the continuation of the team’s pivot towards greater reliance on an efficient attack from set-piece platforms — which was highlighted by The XV prior to the series, and has been well documented since — does feel like we’re starting to get somewhere.

Equally, looking at their domination of the running game in these fixtures doesn’t really reveal anything new.

New Zealand blew their Pasifika opponents away with ball in hand (averaging 731.7 running metres per game), and prevented them from making much ground themselves (conceding 220.3m) — but this was broadly consistent with other recent performances against the same class of opponents.

In their five tests against Tier-2 opposition during the last World Cup cycle, they made 833.8m with ball in hand on average and conceded 304.6m.

However, identifying the continuation of the team’s pivot towards greater reliance on an efficient attack from set-piece platforms — which was highlighted by The XV prior to the series, and has been well documented since — does feel like we’re starting to get somewhere.

This focus — particulary noticeable in the games against Fiji — was a clear departure from their try-scoring exploits against Tier-2 teams between 2016 and 2019.

While they averaged almost exactly the same number of tries per game in the July series (11.3) as they did in Tier-2 games in the last four-year cycle (11.2), a much greater proportion of this year’s scores came directly from scrum or lineout attack.

Where only 2.2 of those 11.2 tries per game in Steve Hansen’s final stretch in charge were scored on the first phase after a set-piece, Foster’s team extracted an average of 4.0 per 80 minutes from this facet of the game.

But even more interesting is the light that these often mismatched fixtures can shine on how a team is trying to develop its approach in phase play.

With more space and time on the ball, a clearer picture of the ideal form of a team’s attacking shape can start to emerge.

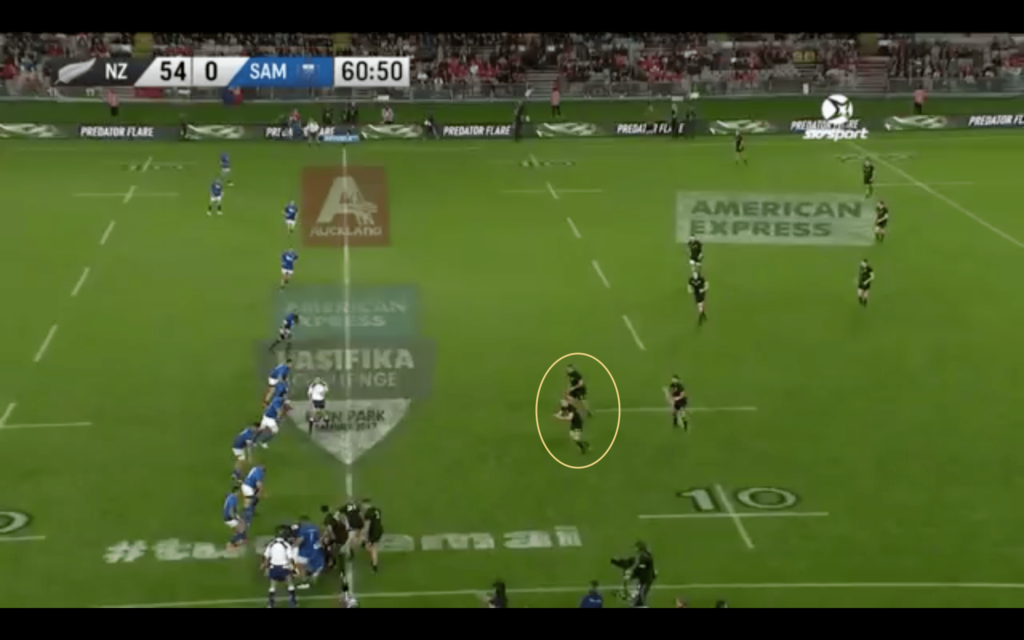

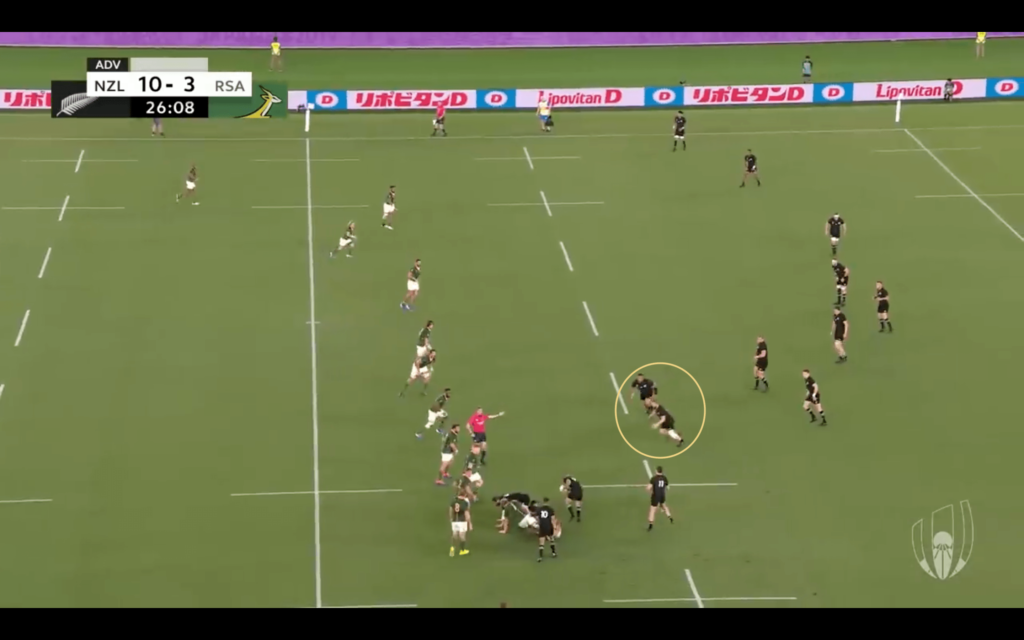

In this regard, the All Blacks’ one-off test against Samoa at Eden Park back in 2017 is an interesting case study.

While the structures they ran with in that game were not put to immediate use in the subsequent test series against the Lions, the deeper shape they began experimenting with from wide rucks — with that distinctive pair of forwards running tight lines off the scrum-half — became (for better or worse) the basis of the team’s primary attacking structure heading into the 2019 World Cup.

So, what new wrinkles have appeared in Foster and attack coach Brad Mooar’s approach in 2021?

Approaching the question statistically, the answer is clear: the extent to which they are spreading the ball from side to side across the field in the possession has markedly increased.

After completing, on average, 139 passes for every 100 carries they made in tests last season, the 2021 All Blacks have made 157 per 100 carries so far this year.

This isn’t just a consequence of playing weaker opposition either: in their five Tier-2 games in the last World Cup cycle, they averaged only 133 passes per 100 carries.

In addition, the way that they’ve imparted this extra width has been particularly revealing.

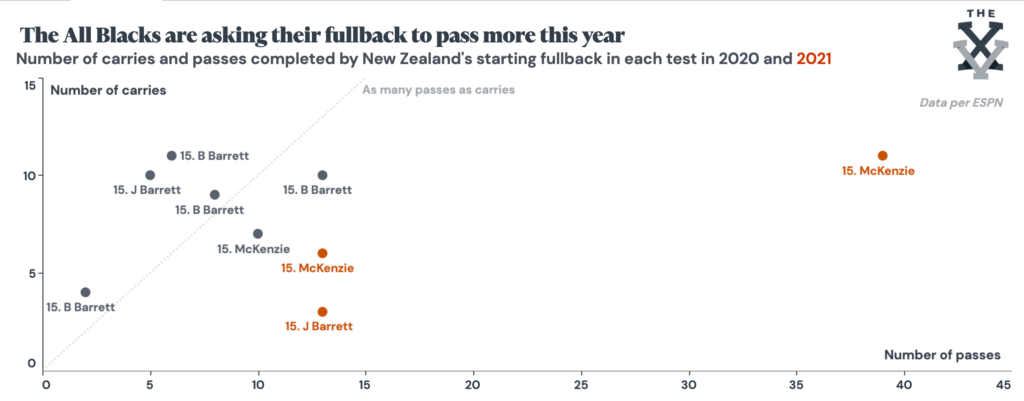

With Beauden Barrett appearing to no longer be considered a frontline option for the 15 shirt, you might have expected the team’s fullback to become less prominent and Richie Mo’unga — at this point inarguably New Zealand’s incumbent first five-eighth — to be given the opportunity to exert even more control over their game.

In fact, they’ve gone in the opposite direction.

Again, this isn’t just a Tier-2 effect: in those five games between 2016 and 2019, the All Blacks’ fullbacks averaged 1.1 completed passes for every carry; this year so far, that ratio stands at 3.3 to 1.

Damian McKenzie has started two of their three games so far at the position, and — while at times he struggled physically against the Fijian defence — the sheer variety of situations in which he popped up across the field during the series was encouraging.

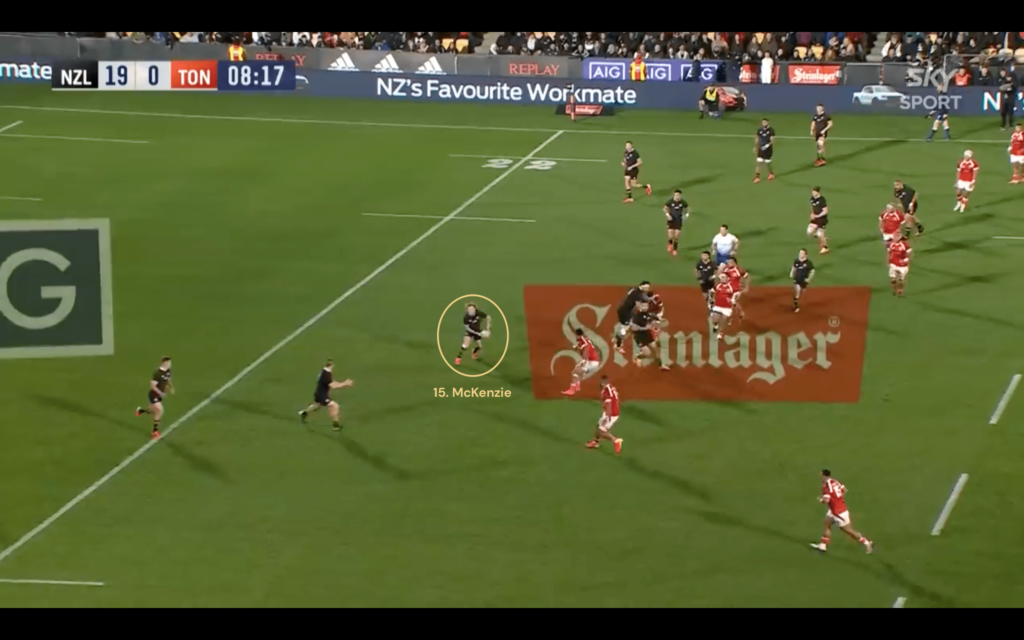

The Tonga game at Mount Smart Stadium — where he was involved right from the off — exemplified this well.

By the ten-minute mark, he had stepped in at first receiver on the left-hand side to set George Bridge free on the edge…

…slipped outside Mo’unga at second receiver and provided a pass to Will Jordan before he sliced through the defence…

…and swept late into shape on the outside shoulder of centre Rieko Ioane to link play between the midfield and the tramlines:

All three of those interventions were in the lead-up to All Blacks tries — and, by the time the game had finished, the diminutive playmaker had provided important touches of the ball in the build-up to seven more of the team’s scores.

McKenzie is obviously very comfortable in the 10 shirt himself, so the coaching staff scheming these sorts of involvements for him isn’t necessarily surprising.

However, even when Jordie Barrett — a comfortable distributor, but less of a natural than McKenzie — started at fullback in Dunedin, they looked to introduce him into the game early in similar ways.

In one of the All Blacks’ first attacking sequences at Forsyth Barr Stadium, Barrett popped up close to the breakdown and nudged an accurate crossfield kick into space on the right touchline — almost creating a score for winger Sevu Reece in the process.

With Beauden Barrett no longer clearly first-choice at the position, there might be fewer headlines about ‘dual playmakers’ in New Zealand this year — but if this trend continues, it’s a strategy that could become even more crucial to the All Blacks’ fortunes in the Rugby Championship and beyond.

Based on the evidence we have so far this year, it therefore seems as if Foster and Mooar will be trying to get their 15 more involved — regardless of who they select in the role.

With Beauden Barrett no longer clearly first-choice at the position, there might be fewer headlines about ‘dual playmakers’ in New Zealand this year — but if this trend continues, it’s a strategy that could become even more crucial to the All Blacks’ fortunes in the Rugby Championship and beyond.

For a number of reasons, we should always treat what we think we have learned about international rugby with a healthy dose of scepticism. At the same time, however, it’s more important than ever to try and make the most of what scarce information we have to try and understand the game as best we can.

In the case of the All Blacks, the past has shown us that there can sometimes be meaningful clues hiding in plain sight during their matches against weaker opposition — if you can find it in yourself to look past the lopsided scorelines.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free