When you watch Damian McKenzie hare around Waikato Stadium with his characteristic effervescence, it is easy to forget that he is now — as he begins his seventh season of Super Rugby — a Chiefs veteran.

The South Island native made his debut for the franchise at the start of the 2015 season under the watch of title-winning head coach Dave Rennie, and quickly gained a reputation for enterprising attacking play and electric footwork.

McKenzie also formed effective combinations with like-minded players across the backline. His ability to link with halves Brad Weber and Aaron Cruden on his inside and wing James Lowe on his outside turned the Chiefs into one of the most devastating teams in the competition in broken play.

But top-level rugby has evolved significantly in the six years since McKenzie made his Chiefs debut — and not necessarily in ways that suit his own game.

Even Super Rugby — which has traditionally seen more ball-in-hand, end-to-end rugby than Northern Hemisphere club competitions — has not been completely immune to the growing influence of more organised and aggressive defensive strategies.

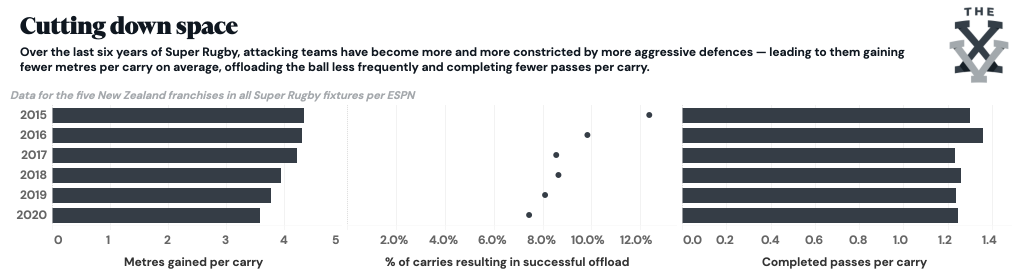

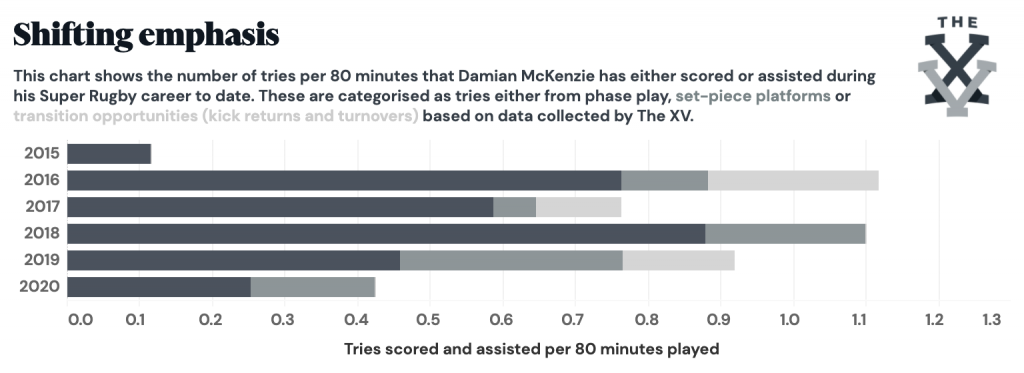

By examining a number of different performance metrics over this period, we can see how the shape of the game on the field has changed.

As the charts above show, the average number of metres gained per carry by Kiwi teams in Super Rugby decreased by nearly a fifth between 2015 and 2020. Meanwhile, the frequency of their successful offloads declined by two fifths, and the number of passes they completed per carry also fell.

This change will have been partly due to alterations to the structure of the competition over the same period. Rather than playing against a range of teams of varying defensive quality, since mid-2020 franchises from New Zealand — consistently among the strongest in the wider competition — have been facing off exclusively against one another.

However, the primary cause is likely to be a broader shift in the strategy of defending teams. Attackers are being closed down more quickly, and no longer have the time to carry as far over the gain line or pass the ball onward to another player. There is now also a clear focus from defending sides on getting two players into the tackle, to ensure that the team without the ball dominates the collision.

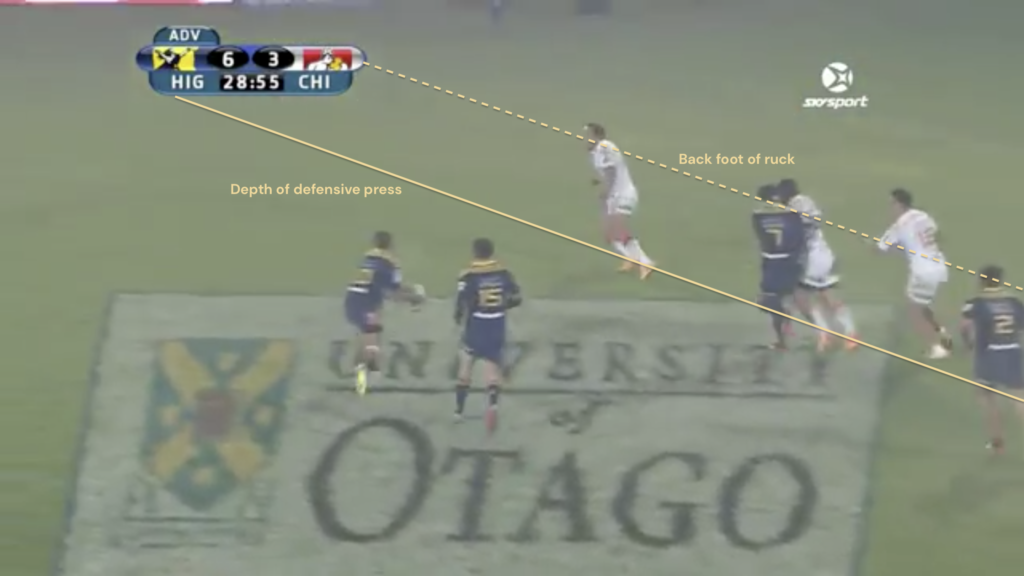

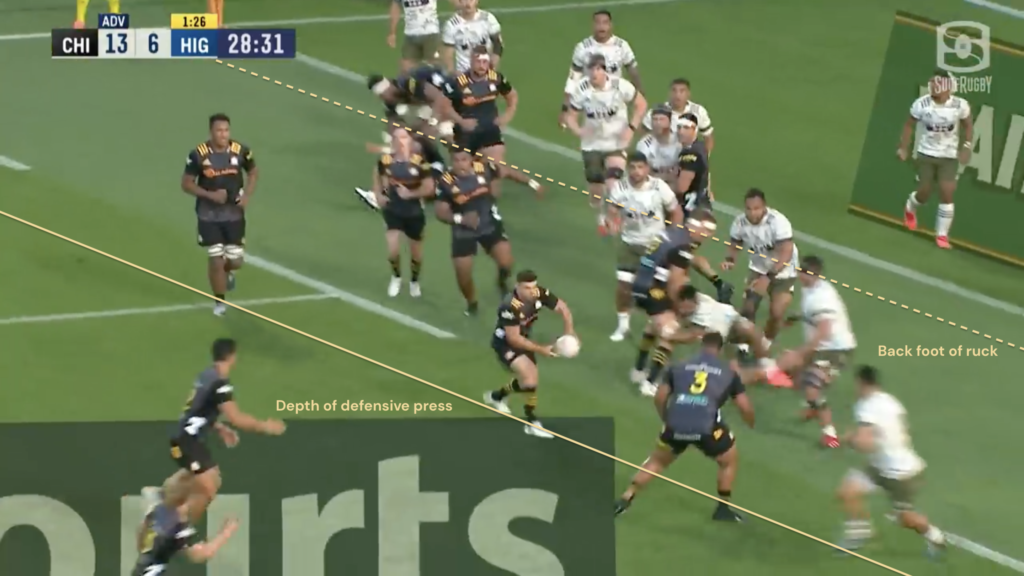

A comparison of two similar sequences of play in Super Rugby matches between the Chiefs and Highlanders — one in 2015, and one in 2021 — serves to illustrate this change in strategy.

In both instances, the attack has played toward the openside from a ruck beyond their opponent’s 22m line, with a forward playing a screen pass to their fly-half. In the first sequence, the Chiefs drift rather than press Lima Sopoaga, the Highlanders’ 10, after he receives the ball.

In contrast, in the second sequence — from the Chiefs’ fixture in Round 2 of Super Rugby Aotearoa this year — the Highlanders’ midfield presses aggressively. By the time Chiefs No 10 Bryn Gatland sets to release his own pass, there is already a defender level with him.

These changes haven’t completely eliminated McKenzie’s value as an attacker — in the second example, he was able to take advantage of the Highlanders’ aggression with his sharp footwork and score under the posts — but have constrained his game in some ways.

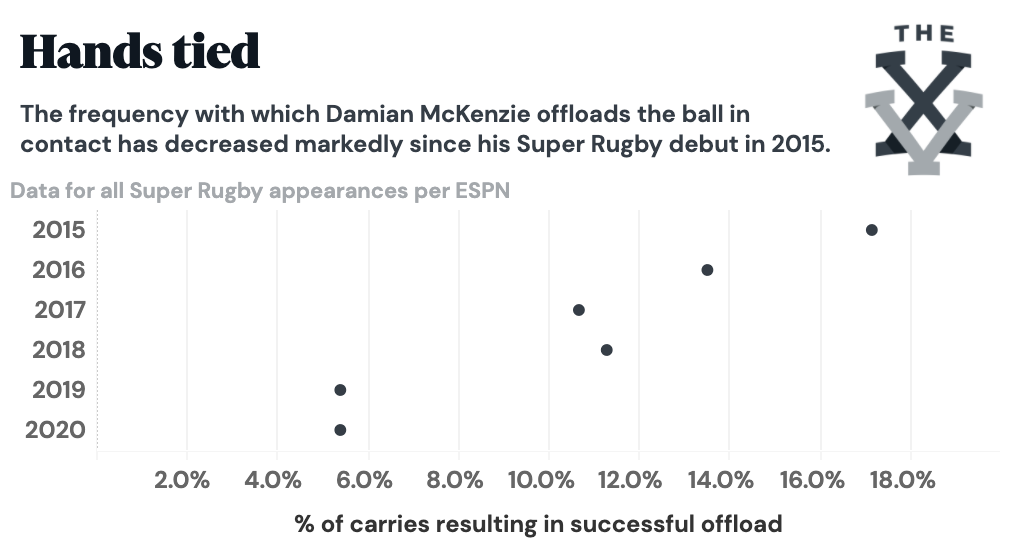

His offloading ability, for example, has been hit hard. While he was able to complete successful offloads more frequently than the average Kiwi player in Super Rugby for the first four years of his career, this rate has fallen off significantly since 2018.

Improved defensive organisation has also impacted his effectiveness in transition situations.

These often arise after a team receives a kick in open play, but more coordination from kicking teams as they chase upfield — as well as more precise and accurate kicking strategies — has allowed the side giving up the ball to control those moments in the game much better.

Turnovers conceded by opponents can also create opportunities to attack in transition. However, since the start of McKenzie’s career, teams’ ability to hold onto the ball for sustained periods has improved across the board. The Chiefs conceded a turnover once every 9.1 carries in 2020, compared to the 2015 Chiefs’ rate of once every 6.1; their opponents in 2020 conceded a turnover once every 9.9 carries, compared to their 2015 opponents’ rate of once every 6.2.

To illustrate how much of an impact this has had on McKenzie, consider these figures.

In the 3,412 minutes he played for the Chiefs under Dave Rennie between 2015 and 2017, he either scored or assisted six tries on the first phase of a possession after an opponent’s turnover or open-play kick. However, in the 2,558 minutes he has played under Colin Cooper and Warren Gatland since 2018, he has been involved in only one such score.

It’s clear that, even in Southern Hemisphere club rugby, structured attack is taking on much more importance than ever before – and McKenzie is having to adjust his game as a consequence.

Getting the best out of McKenzie in 2021 is not necessarily a question of whether he plays in the 10 or 15 shirt; in practice, that distinction is becoming less and less important.

Young playmakers Zarn Sullivan of the Blues and Ruben Love of the Hurricanes recently spoke to The XV about the similarities between the two positions in attack, while All Blacks head coach Ian Foster told Sky’s The Breakdown earlier this year that he is “a big believer that [McKenzie] can play 10, and the skillsets he shows at 15 are transferrable”.

Rather, regardless of the number he has on his back, deriving value from McKenzie is a question of whether or not you can manufacture situations in which he can best use his unique set of attacking skills.

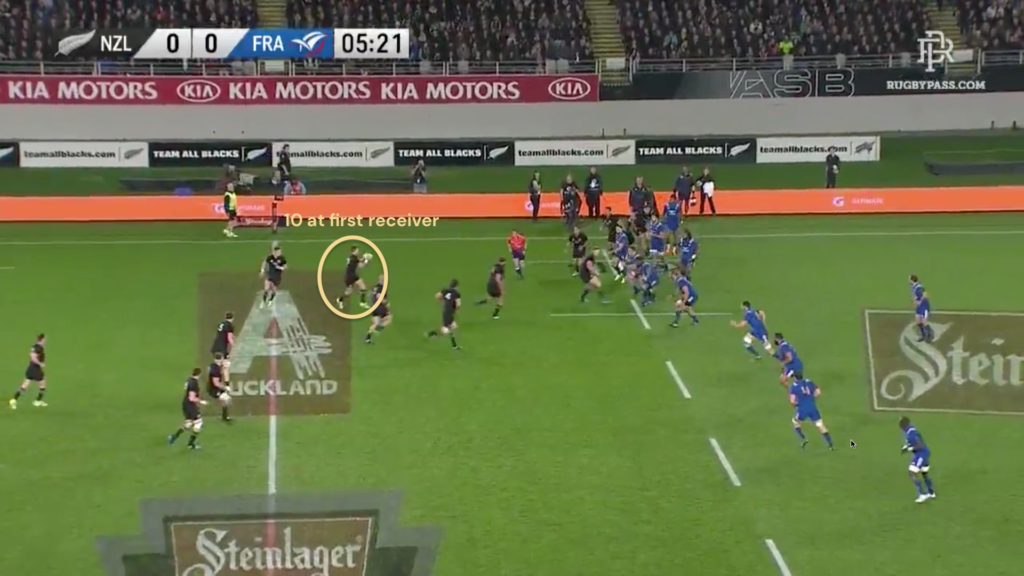

Even when starting at fullback, he is often employed by the Chiefs in phase play in the traditional roles of a first five: distributing after receiving a pass directly from his scrum-half, or trailing a pod of forwards to take a screen pass.

McKenzie is a more than capable distributor from first receiver himself, but it is that second shape in which he poses a real threat — and which the Chiefs could benefit from running more regularly.

Back in June 2018, Foster himself showed the impact that McKenzie can have if you build a team’s attack around his role in that shape.

After Beauden Barrett’s injury early in the second test of their series against France, McKenzie became the All Blacks’ frontline 10 — and, in his role as the assistant coach in charge of the team’s attack, Foster altered their approach to suit his new fly-half’s strengths.

In the first test of that series, New Zealand attacked in phase play using the structure they took all the way through to the 2019 World Cup (and the start of their 2020 campaign). This set-up had Barrett playing behind a pod of forwards from wide rucks, but receiving the ball directly from 9.

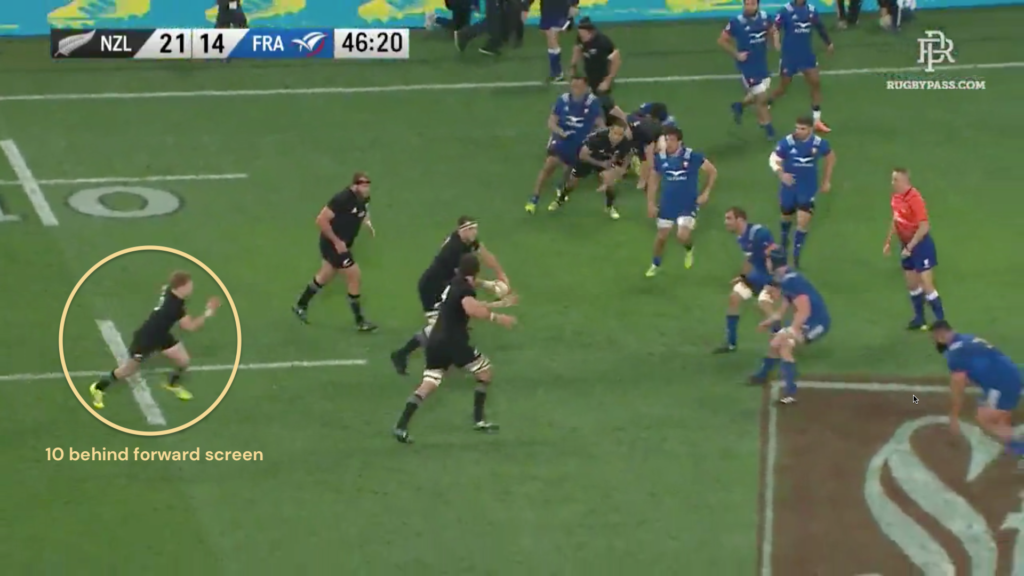

By the time McKenzie had run out to start the third test, however, the All Blacks had moved some pieces around to suit his game.

In contrast to the example above, at a number of wide rucks Foster had his new 10 taking a screen pass from a forward.

This allowed him to attack the line at pace and identify mismatches. In the example above, for instance, he scorches around the outside of tighthead prop Uini Atonio for a clean break, before beating the backfield cover for a superb solo score.

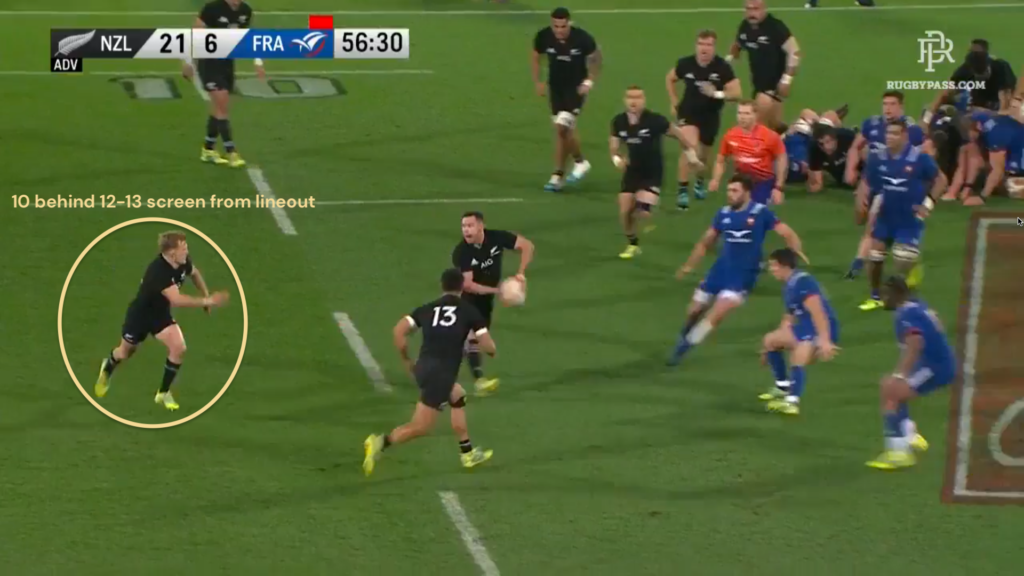

Set-piece attack is the other area of structured play that has become more prominent in professional rugby over the course of McKenzie’s career, and in that series New Zealand drew up a number of attacking plays from lineouts that used the threat of McKenzie’s running game to great effect.

In this example from the second test, after setting up a maul from a lineout, the All Blacks use a variation on a set-piece shape that is now incredibly common across the world.

Their 12, Ryan Crotty, takes the ball at first receiver, with McKenzie — on as a substitute at 10 — fading out behind the run of 13. In this instance, he is the strike runner himself, and gets to the outside of Mathieu Bastareaud for a clean break.

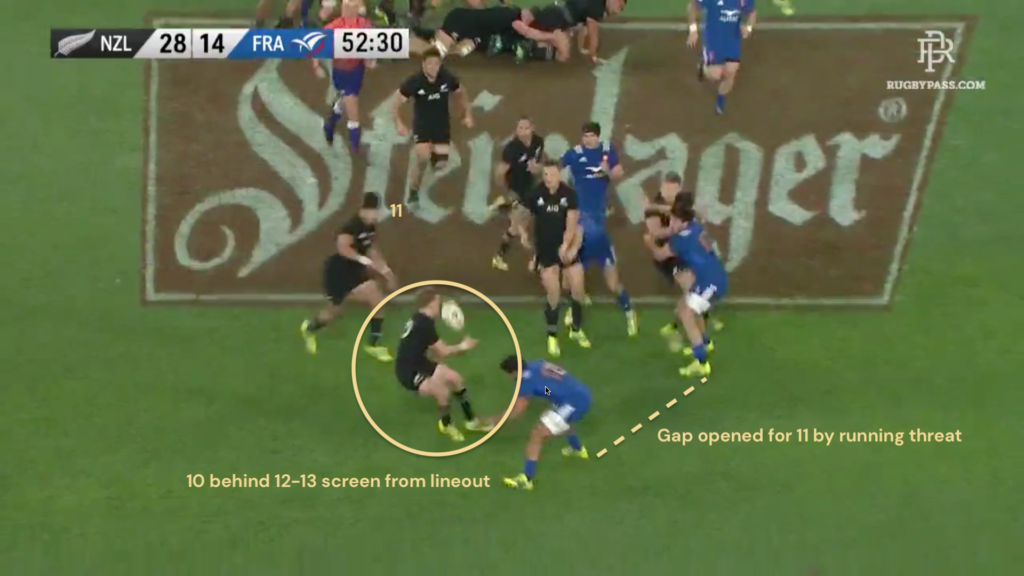

Having shown France that McKenzie is a running threat, in the third test New Zealand came back with a twist on the same basic set-up.

This time, the French midfield is much more active in trying to close McKenzie down — but, in their eagerness to remove that option, leaves a hole into which the fly-half can play blindside wing Rieko Ioane.

While those test matches against France are now almost three years in the past, the methods that the All Blacks successfully used to bring McKenzie into the game are still close to the cutting edge – and that series should be the blueprint for the Chiefs to get the most out of their star playmaker, regardless of which shirt number he wears.

Given the ways in which top-level rugby has changed since the beginning of his career, doing so is no longer as simple as letting him roam around the field and pick teams off after turnovers or loose kicks. However, if the Chiefs are clever with how they use McKenzie in their structured play, then he can still be an incredibly dangerous attacking weapon.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free