In August 2012 I spent a day in Toulon observing Jonny Wilkinson conduct a mentoring masterclass with two young British players, part of a now defunct project called the Jaguar Academy of Sport.

The two tyros were Matthew Screech and Jack Walker, both of whom have been capped by Wales and England in recent seasons, suggesting that Jonny’s pearls of wisdom were not wasted.

They certainly weren’t on me. The day gave me a fascinating insight into what made Wilkinson such a formidable player; we can all probably agree that there have been more naturally gifted players to have played for England, but surely none had Jonny’s mental strength and that legendary perfectionist streak.

As I recall, the masterclass ran somewhat over time, such was Wilkinson’s attention to detail, and it was a mad rush for everyone to get to the airport for the flight back to Blighty.

What also stands out in my mind from those 24 hours was the evening of our arrival. We watched Toulon playnewly promoted Mont-de-Marsan in their final summer loosener before the start of the Top14 season; afterwards we dined at the official Toulon brasserie in the bowels of the Stade Mayol. It was packed with punters and service was slow for the table of Brits in the corner. Then Wilkinson arrived, just a fleeting visit, to say hello to Screech and Walker, and confirm the timing of the masterclass the next day. But Jonny was there long enough to be seen by the waiting staff. We were friends of Jonny’s! Boy, did their attitude change. They even brought out a complimentary tray of patisseries at the end of our meal.

Jonny had that effect on the French. Two years later I was among the 80,000 crowd at the Stade de France for his last ever game. It was the Top 14 final and Wilkinson’s four penalties and a dropped goal secured Toulon’s first domestic title in 22 years. In the minutes after the final whistle something remarkable happened; ‘God Save the Queen’ was blasted out on the stadium tannoy, and tens of thousands of French fans – regardless of what team they supported – sang along. The next day the mayor of Toulon made Wilkinson an honorary citizen of the city: not even the Queen was accorded that accolade.

Wilkinson still crops up from time to time in French adverts, most recently last year when he gave his take on ‘Le Crunch’ for a well-known bank. He digressed, explaining why his five years with Toulon were so important. “It was something really positive for me,” he said, speaking in French. “But the most significant aspect was that it connected me to the French people. I received a warm welcome and a lot of support, not because I kicked penalties or helped win matches but because I was there and part of their team. That enormously changed my view of French rugby.”

It also changed the French perception of English rugby. Before Wilkinson signed for Toulon in 2009 few Englishmen had ventured across the Channel, far less made a success of their stay in France. In the amateur era Nigel Horton and Rob Andrew had spent a season with Toulouse, and the England and Lions lock Maurice Colclough had had a brief spell with Angoulême.

One or two others had tried their luck in the professional era, such as Dan Luger and Alex King, but the only two who could claim to have carved out a successful career were Richard Pool-Jones (capped once by England in 1998) at Biarritz and Stade Francais in the 1990s, and Perry Freshwater, a member of the 2007 World Cup squad, and now in his 20th year at Perpignan, half as a player and half on the coaching staff.

In his five seasons on the Côte d’Azur Wilkinson was rarely injured. He played in 141 games, scored 2055 points and won two Champions Cup titles and the Top 14 trophy.

With no disrespect to Pool-Jones or Freshwater, neither was a marquee signing. But Wilkinson was. When it was announced in May 2009 that he’d signed for Toulon there were gasps of astonishment among some French journalists. No one doubted his talent – not least because he had been instrumental in dumping France out of the two previous World Cup semi-finals – but many questioned his durability. Between 2004 and 2009, Wilkinson had spent 38 months out injured, and it was wondered whether the Toulon owner, Mourad Boudjellal, wasn’t wasting his money (reputedly €800,000 a season) on the England fly-half. When that question was put to Philippe Saint-André at the press conference to announce the deal, Toulon’s director of rugby replied: “Of course, he’ll undergo medical tests. We want him to be 100%.”

Perhaps it was the Mediterranean climate that healed Wilkinson’s wounded body, or perhaps he was better managed by the Toulon medical staff. Whatever the cause, in his five seasons on the Côte d’Azur Wilkinson was rarely injured. He played in 141 games, scored 2055 points and won two Champions Cup titles and the Top 14 trophy.

Aside from the rugby pitch, Wilkinson was rarely spotted in Toulon. He lived twenty miles west of the city centre, deep in the countryside, and he didn’t frequent the bars or seafood restaurants that line the quayside close to the Stade Mayol. But he wasn’t aloof. He just prized his privacy. On Wilkinson’s retirement, a Toulon supporters blog tried to explain why this shy, almost ascetic Englishman, had so won their hearts. “Wilkinson has become part of our lives not because he resembles us but precisely because he is in every way different from us,” it said. “The people of Toulon speak loudly, with their shirts open and their chests puffed out, whereas Jonny is all restraint and closed buttons. And it is precisely because they are intimidated by this austerity, which is not theirs, that the people…have a deep admiration for the man.”

This admiration extended beyond Toulon to the rest of France, and it was why the bank, Société Générale, signed up Wilkinson in 2015 to be their international ambassador, a role he still performs; he is to the French the embodiment of rugby’s ‘valeurs’, the ultimate team player: selfless, hard-working and humble.

Sorry, good game. This phrase sums up the arrogance of the rugby player from across the Channel, hidden under a veneer of fair play.

Liberation newspaper

Ten years ago the newspaper, Liberation, listed five reasons why France should like English rugby; Wilkinson was No1, he with the “face of an angel and the cold blood of a hired killer”, who kicked “1,000 penalties in a week of training to prepare for the 20 or so attempted in a match at the weekend”.

Their respect for Wilko was matched by their disdain for an earlier golden boy of English rugby, Will Carling, who was No2 in Liberation’s five reasons why the French should dislike English rugby. He epitomised the swaggering, stuck-up Anglo-Saxon, who coined the phrase ‘Sorry, good game’, a phrase selected by Liberation as the No 1 reason to dislike the English. “This phrase sums up the arrogance of the rugby player from across the Channel, hidden under a veneer of fair play,” raged the paper. “Accompanied by a smirk, it was the haunt of a lot of French players in the 80s and 90s, knocked out by the soporific – but often winning – game of the English.”

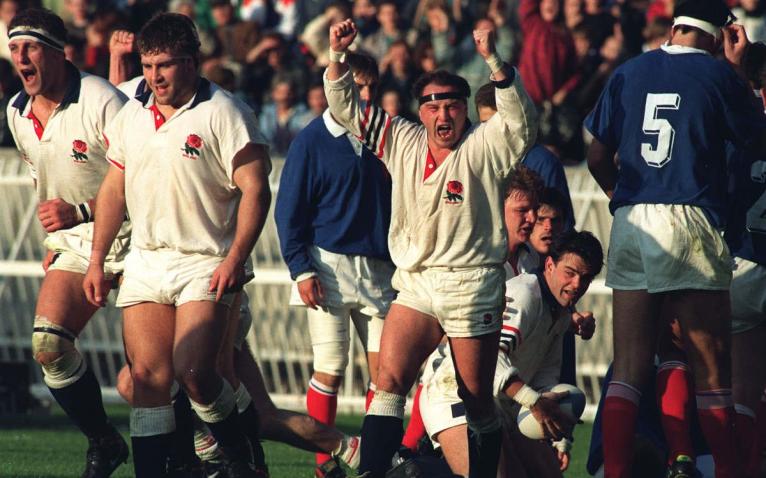

Other than Carling the paper didn’t name names, but presumably they had in mind Brian Moore – who in 1995 famously said that ‘playing France is like facing 15 Eric Cantonas; they are brilliant but brutal’ – Mickey Skinner, Wade Dooley, Dean Richards and Peter Winterbottom. They were all present at the Parc des Princes in February 1992 when rugby relations between France and England hit rock bottom. England won the match as France lost the plot, along with two of their front row, Vincent Moscato and Gregoire Lascube, shown red cards for acts of aggression.

Rugby, and the world, is unrecognisable from that day in 1992. It was a time before the Champions Cup, the internet, Eurostar and cheap air travel, when far fewer Brits travelled to France and vice-versa. We knew little of each other, beyond what we saw in films and read in books, and that allowed lazy stereotypes to flourish in rugby – that of the cold and arrogant Englishman and the wild, hot-blooded Frenchman. Even when the likes of Jason Leonard and Philippe Saint-Andre arrived on the scene, the cliches couldn’t be challenged.

It wasn’t until this century that perceptions began to broaden. Raphael Ibanez and Serge Betsen became cult heroes at Saracens and Wasps, just as Wilkinson did at Toulon (and now Zach Mercer at Montpellier).

As a result England versus France matches have lost some of their, dare I say it, bite. It turns out that – in rugby’s case, at least – it was unfamiliarity that bred contempt.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free