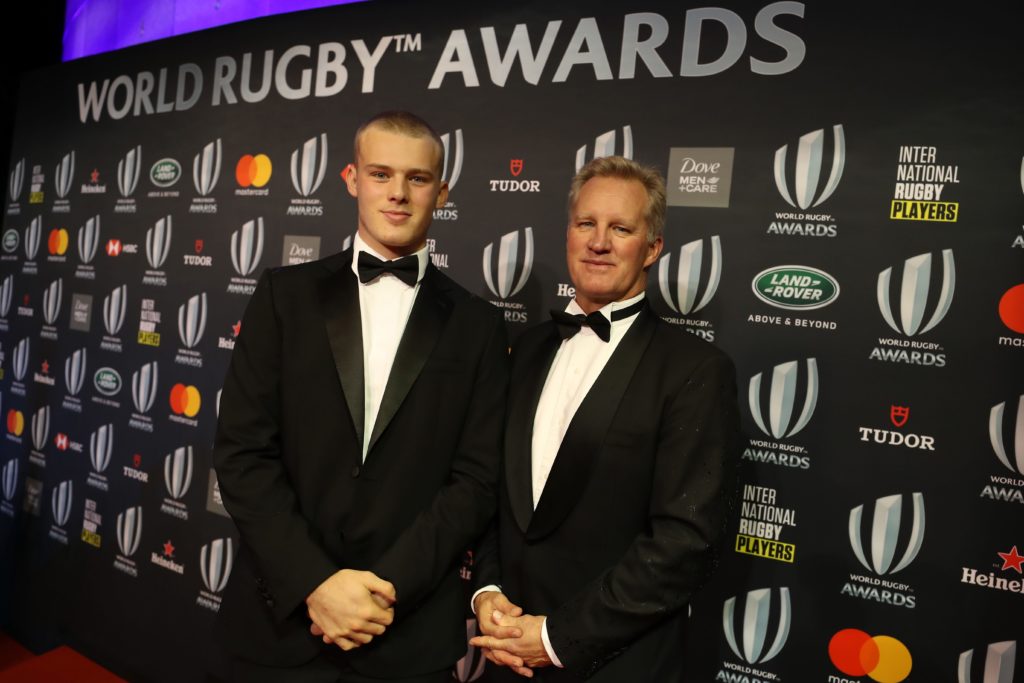

Lewis Ludlam, the England and Northampton Saints loose-forward has given my question some thought. “I would say being a dad is about your actions, not your words; what you do, not what you say.” The reason for the deliberation is simple: he’s answering in front of his father. Arron Ludlam occupies the other half of my zoom-call screen. The head and shoulder outlines are strikingly akin: the lean of the head, the shape of the nose, even their voices leave a comparable imprint on the ear. Gifts bestowed without consent; burdens carried without reproach.

I had been speaking to Lewis about a few things before the subject of ‘Dads’ arose. He’s an erudite young man. Ten minutes in his company and you can easily pick up what Eddie Jones sees in him. He is thoughtful and passionate, able to find the right words, the right cadence, and whilst his conversational style doesn’t match the boisterous way he tumbles through tackles, you can see the same drivers are in place.

Much of that is down to his father. Arron Ludlam is the son of an immigrant child. His mother came to the UK via Palestine, Lebanon and Cyprus. Growing up for him was happy but challenging; he had to work hard for his chances. His relationship with his own English father was tricky and indeed, he hasn’t spoken to him for ten years, so there is a sharp focus on his own parenting. He supports all of his children’s endeavours equally; there are three Ludlam sisters (with busy schedules) and Arron has a stepson in the Saints Academy. He says he is ‘always on his way somewhere’.

Both Ludlams talk openly about the candour that sport creates. How it can break you down, make you vulnerable, and how you have to build yourself back up. They outline challenges with their mixed heritage backgrounds; how today’s political climate makes it easy to be misunderstood but how important their voices, and those of players like Ellis Genge, are. They also talk about their own relationship as one that occasionally carries disagreements, but always comes back together; family meals are a must. Large get-togethers that sometimes extend to other players too. Emmanuel Iyogun, a school friend of Ludlam’s sister at St Joseph’s, was on his way to a Ludlam barbeque before getting a call from Saints to make his debut, the week before his eye-catching European display against Exeter.

I like to follow the boys from less traditional backgrounds. England have a massive resource at our disposal and if we could tap into that, we would be the strongest team in the world.

Arron Ludlam, father of Lewis

“In the past few years I’ve been doing my refereeing badges and got to know those lads through reffing at St.Joe’s. When Lewis was playing in the Six Nations versus Scotland, Manny was playing the night before for the U20s. We went to watch him. I like to follow the boys from, let’s say, less traditional backgrounds. England have a massive resource at our disposal and if we could tap into that, we would be the strongest team in the world. The game needs to find ways to be more inclusive and embrace even more diversity. We’re not doing the wrong things at the moment, we just need to do many more of the right things.”

Arron played semi-pro football and boxed at white-collar amateur level; he played his first game of rugby at forty years old and wished he’d done it earlier. He was always incredibly competitive and prided himself on a hard edge as a boxer. Lewis was old enough to watch his dad fight; watch him get hit yet finish a relatively short career unbeaten. But as Lewis found his love for rugby, Arron recognised that his son was heading into a sport he didn’t fully understand. That may have been a blessing in disguise.

“I’d coached Lewis’ football team when he was twelve. I cringe when I think of some of the things I said and did. Telling him what he needed to do on the pitch; showing him how he needed to play. With rugby, I knew very little and therefore ended up asking him questions. I encouraged Lewis to talk about his solution to a problem; ‘How did you think it went…?’ ‘What do you think you could do better?’ I didn’t have any other choice but looking back, I think this process was very beneficial. The father son dynamic is difficult enough without the added pressure that sport brings. I wasn’t telling him things, so he was able to find his own way.”

“Nowadays it’s a little bit different. I send him WhatsApps! Like ‘just relax and have fun’ or ‘try and express yourself’; Lewis is so much better when he’s enjoying himself on the pitch. And here’s a funny thing: before games I would always send him one of these messages and they would obviously pop up on his phone, but they would never be ‘read’; the two little ticks would always remain grey. After a while I thought, ‘Maybe he’s not reading them?’ So before the Saints Lyon game in the Champions Cup, I decided not to send him one. Thought maybe he didn’t need it; I was getting in the way. And you know what? About two hours before kick-off, he phoned me, almost panicking: ‘Is everything alright? What’s going on?’ Turns out he was reading every one. That’s an accurate representation of being a dad, eh? The little things, the things you don’t think are working, they’re often the most important.”

Ludlam’s teammate James Grayson has a rugby dad: Paul played for the same team, on the same ground and in the same position as his son, with impressive effect. Father and son look hauntingly similar in black, green and gold. James was tottering around Franklin’s Gardens from the moment he could walk. One of his first memories is running amok in the physio’s room and twisting the dial on Nick Beal’s TENS machine to maximum and watching the famous fullback’s face contort. James has always been around rugby; always wanted to play rugby like his dad. I wonder if that came with any difficulties.

“It was pretty much all positive,” the young Saints fly half explains. “The difficulties came when people said I’d only achieved things because of my dad; that I was only picked because of him. Didn’t matter the sport, people would say that I was only in the team because of who my dad was. That wasn’t nice, but it only served to make me tougher, more resilient, more hard-nosed.”

I am very lucky. I can talk to my dad about pretty much anything, and I do. Not just the technical areas of the game or tactics; we talk about emotions and how I feel

James Grayson, son of Paul

“I am very lucky. I can talk to my dad about pretty much anything, and I do. Not just the technical areas of the game or tactics; we talk about emotions and how I feel. That is a huge benefit. To have someone recognise that. He talked to me about how he felt before the All Blacks game, where they drew 26-all; how he felt so desperately nervous. It’s kinda what you need to hear, that what you are going through is not unusual. Sometimes you just need someone to say, ‘I know how you feel’.”

Grayson Junior was a prodigious multi-sport talent, playing for Northamptonshire 2nds at cricket as recently as last year. He also played hockey, basketball, volleyball, tennis and golf as a school boy; everything was beneficial.

“You have to play lots of different sports for as long as you can. Sam Vesty (Saints Attack Coach) is very keen on bringing in all sorts of different balls for us to train with, keeping our hand eye coordination as sharp as possible. Dad would encourage me to play them all.”

“It’s about facilitating; nothing more. Try not to put too much pressure on. They need to enjoy it. That’s the most important thing. It was all fun for me; my dad and I had a few tough conversations, especially around sixteen when contracts started being handed out. I remember one car journey back from a match was in total silence because he’d been pretty honest about how I’d played and I was angry at him. But he was right, and I knew that, deep down. But he never pushed. He advised and helped, but he never told me I had to play.”

I wonder if father Paul had ever offered any key bits of advice?

“Not one major piece; there have been so many, over the years. But in my last game, for instance, I just got a text, which read: ‘Give it the beans’. So it’s not advice, just support. He’s with me. That’s all I need to know.”

And that is an angle I explore with a person who has a very famous rugby dad. Rhys Edwards’ father was arguably the greatest player ever to play the game; a man who scored ‘the greatest try’. Surely Sir Gareth would have handed down all the crucial secrets.

My grandfather, my dad’s dad, was a coal miner, like his father before him; he gave my father no rugby advice. He just loved and supported him; not because he was really good at rugby, but because he was his son. Like my dad did with me. I bet Dan Carter’s dad is just the same.

Rhys Edwards, son of Gareth

“People always ask me that,” begins Rhys, mentally rewinding the years. ‘Like me and my older brother had this magical childhood, full of backs’ moves and spin passes. It was genuinely nothing like that. He was more likely to come and kick a football around with us, try and stick one past me in goal. He was just our dad. We knew that he was famous; we went with him to games sometimes and saw all the people trying to talk to him, but there was no pressure on us. It’s difficult to explain because we knew no difference, but it was just normal.”

“I’m still good friends with Dai John (Barry’s son). We spent a lot of time together growing up and we’ve never spoken about this: about growing up with a famous rugby dad, and if it ever affected us: it wasn’t a thing. There was no expectation from our fathers.”

“Maybe it’s different for those families who have the potential of professional rugby playing sons: when it becomes a life choice. That wasn’t there for me. But I’m a dad now and I think most of the job is logistics. Getting them where they need to be. I suppose there are some dads who encourage, some who give out tough love; who are critical; full of do this, do that. But I’m not sure what that does; does that make the player better? My grandfather, my dad’s dad, was a coal miner, like his father before him; he gave my father no rugby advice. He just loved and supported him; not because he was really good at rugby, but because he was his son. Like my dad did with me. And I bet Dan Carter’s dad is just the same!”

And talking of Antipodean greats, we leave the last word to a world-conquering Wallaby. Michael Lynagh is regarded as one of the game’s best, a magician for club and country; he also has three sons, Louis, Tom and Nicky, in the Harlequins Academy. Who better to ask about what to say to a young rugby mind?

“Experience is the best teacher. I say nothing more than ‘enjoy it’. It sounds very cliche but if you don’t have fun, then what’s the point?

Michael Lynagh, father of Louis, Tom and Nicky

“Experience is the best teacher. I say nothing more than ‘enjoy it’. It sounds very cliche but if you don’t have fun, then what’s the point? Especially when you’re young. Just let them go. Allow others to do the talking because that is very much part of the process: being able to listen and form relationships with coaches. Maybe there’s been times when I’ve said ‘What else could you have done then?’ or ‘Where would it be best for a fullback to stand in that situation?’ but that is all. Getting them to think is very important. But most of the time, I just watch and say well done.”

A brilliant distributor with ball in hand, Lynagh speaks lucidly about growing up on the Gold Coast in Australia. How surfing was his big love as a young boy and how union was a very late addition to a sporting and supportive household; how only a move to Brisbane late in his childhood gave him a pathway into the sport. He also outlines how his parents encouraged both him and his sister to have a go at everything and how that is very much part of his own parenting now. To give all his boys a chance to enjoy every moment youth gives them.

“Confidence is really important. There was this one time, and I hope he won’t mind me saying, where our middle boy, Tom, was really low on self-esteem. He was 11 or 12. His confidence was shot. Maybe it was the expectation a little, I don’t know, but he came to me and said, ‘I want to play for the Bs’, So I phoned up his school coach and asked him to put Tom in the Bs, and reluctantly, the coach did. Tom played really well; his team won the B tournament and he came back so happy. Not everything is about playing for the best team. You can get so much from just feeling good about where you are.”

Lynagh’s eloquence oozes through. His Australian lilt as honeyed as it is honest. He echoes previous comments about playing every sport and not committing to one too early. He tells stories about positive text messages, unkind comments from others, light touches and not really being able to say anything that will have any sort of lasting effect. He describes three very different boys, with contrasting attributes and needs, but sons who are constantly supported and loved. But it is his final story that has the greatest resonance.

“Louis played in a rugby team at school one year that struggled. It wasn’t a good season for all sorts of reasons. And I remember being stood on the side-line as this dad I’d not seen before stalked up and down. He was shouting at the boys, the coaches, the referee; moaning about everything that was taking place. He ended up standing next to me and started to complain to me about the game. I listened as patiently as I could but in the end I said, ‘You’re obviously pretty passionate and knowledgeable, maybe you should get involved and try and help out?’ He looked at me aghast, disgusted that I should even suggest such a thing. “Pah,” he said, ‘I don’t think so. Anyway, what would you know?’”

So the message is as simple and emphatic as that: try not to become a burden as a dad, bring only gifts. And if a World-Cup-winning, record-points-scoring, hall-of-fame-rugby-player isn’t saying anything, maybe you shouldn’t either.

If you’ve enjoyed this article, please share it with friends or on social media. We rely solely on new subscribers to fund high-quality journalism and appreciate you sharing this so we can continue to grow, produce more quality content and support our writers.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free