It was supposed to be easier this time around.

Coming off a second consecutive Webb Ellis Cup victory in 2015, the 2016 All Blacks looked little like their title-winning counterparts from a year prior. Between the final at Twickenham in October and their first match against Wales the following June, Steve Hansen — who continued on as head coach — effectively lost a third of his first-choice side.

Individuals who. between them, had played 32 per cent of the team’s minutes against tier-one opponents in 2015 either entered retirement or headed offshore.

But this didn’t end up mattering a great deal. 2016 turned out to be one of the team’s most successful seasons in recent memory, with New Zealand winning 13 of their 14 test matches by an average scoreline of 40.1 points to 15.8.

At the end of 2019, in contrast, the exodus was much less significant.

Departing players contributed only 18 per cent of the All Blacks’ tier-one minutes in that World Cup year — and that figure included the 358 minutes played by lock Brodie Retallick in 2019, who is now back in the fold after a two-season sabbatical in Japan’s Top League.

And, while Hansen vacated his position, a degree of continuity remained with the appointment of his assistant, Ian Foster, to the head coach role.

All in all, the stage was set for a strong bounce-back year — and, even after the pandemic hit, there was a chance to lay down a clear marker by dominating the restructured Rugby Championship competition.

Of course, that’s not quite how things turned out.

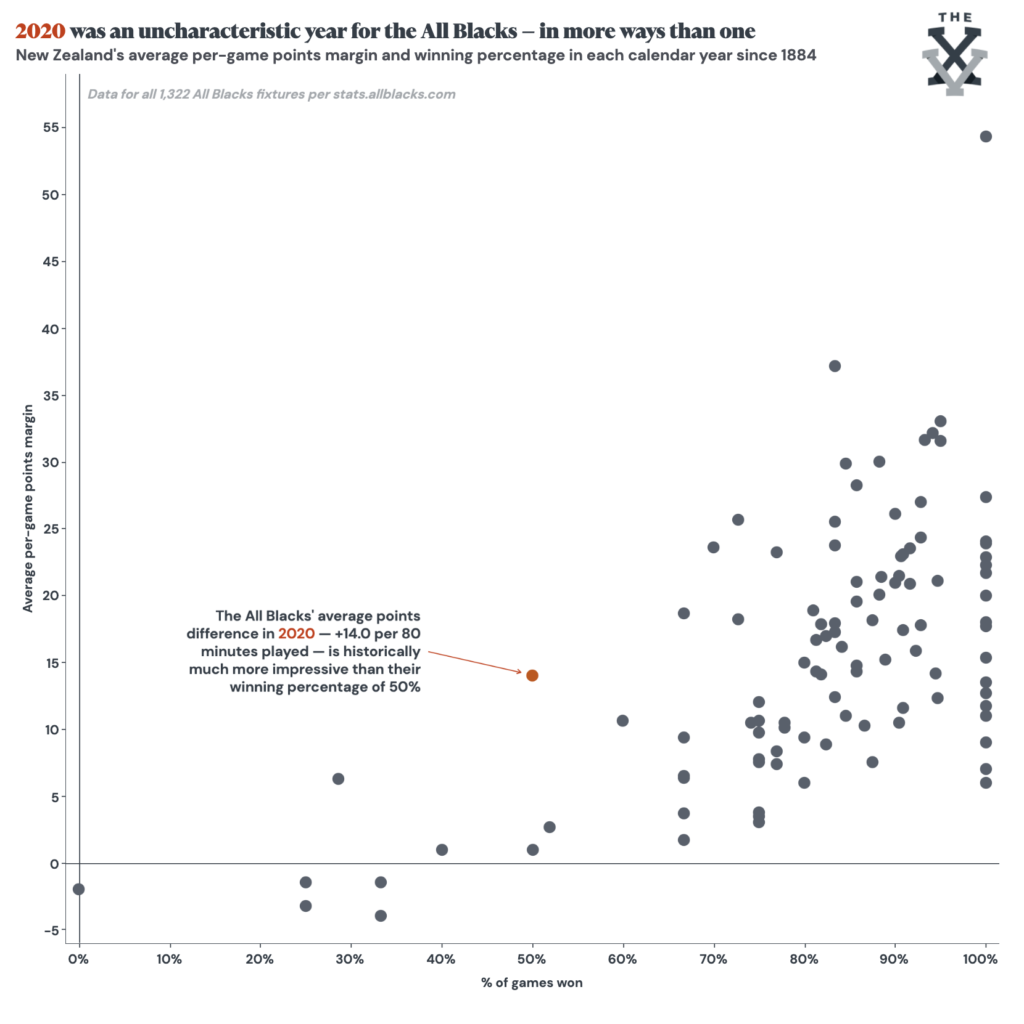

A return of only three wins from six games against Australia and Argentina marred the reputations of both the team and its new head coach, and raised doubts about whether or not they can achieve their stated goal of getting back to the top of the World Rugby rankings by the end of 2021.

However, the picture is complicated slightly by the nature of those three victories they were able to achieve.

Beating the Wallabies 43-5 in Sydney — a couple of weeks after a convincing 20-point win at Eden Park — gave the All Blacks’ a new record winning margin against their antipodean rivals, and the 38-0 win over Argentina in Newcastle was their sixth-biggest win ever over Los Pumas.

Scoring 22 tries and conceding only 7 during the 480 minutes they spent on the field last year also suggests that they are a team with substantially stronger fundamentals than they have been given credit for.

That’s not to say that there weren’t issues with how the team played at times, but — as tempting as it appears to be to some to present a narrative of the All Blacks as a team in inexorable decline — the reality is more complex than that.

And, digging a bit deeper, one of the clearest positive signs for the side’s prospects in 2021 and beyond is the way in which Foster and his assistants were able to evolve the team’s tactical approach in their first year in charge — despite, as John Plumtree said earlier this week, 2020 being an “absolute nightmare” from a planning and logistical perspective.

While the 2019 All Blacks fell short of their ultimate goal of a third consecutive World Cup win, the team that Foster inherited was still clearly the best ball-running side in the world.

Beating the Wallabies 43-5 in Sydney — a couple of weeks after a convincing 20-point win at Eden Park — gave the All Blacks’ a new record winning margin against their antipodean rivals, and the 38-0 win over Argentina in Newcastle was their sixth-biggest win ever over Los Pumas.

In fixtures between tier-one nations that year, they made clean breaks on 11.4 per cent of their carries and averaged a gain of 3.7 metres per carry; between them, the other nine top teams made only 3.0m per carry and clean breaks on 7.4 per cent of their carries in those matches.

But what they sometimes lacked was control over the terms on which the game was played.

The semi-final loss to England is a good example of this: they made 12 clean breaks and 639 metres with ball in hand on 154 carries (compared to England’s 6 and 406m on 147 carries) — but their opponent’s superior territorial kicking game meant that they were often starting these attacking forays from well inside their own half.

A couple of searing breaks from deep got New Zealand out of jail in their group-stage win over South Africa — a game in which they were often battered behind the gain line by the Springboks — but they could not repeat the trick a second time.

Heading into 2020, then, rediscovering that ability to control games tactically —a hallmark of the 2015 side’s run to the title, with Dan Carter at first five — was likely one of the things at the forefront of Foster’s mind. The fact that the head coach described their win over Argentina last November as “methodical” appears to support this.

That control can be established in a number of ways, and the team will have looked to improve their own territorial kicking game — as well as upping their physicality in the contact area to give themselves front-foot ball more frequently.

However, by far the most intriguing shift in this regard was the renewed focus the team put on their attack from scrum and lineout platforms last year.

As it has become more difficult to progress the ball upfield in phase play at test level, set-piece attack has become even more crucial.

Foster and Plumtree — his forwards coach — focused much of their attention on the maul last year. After setting 2.0 successful mauls per game on 8.2 won lineouts in tier-one fixtures in 2019, the All Blacks set 6.2 on 14.0 lineouts in 2020 — and a number of their tries came from playing off this platform.

Clean ball off the top of a lineout, released from the back of a forward-moving maul or passed from the base of a solid scrum allows the team in possession to dictate the tempo of a sequence of play — and the additional five or ten metres required to be covered by the defence usually forces them to sacrifice either line speed or line integrity.

Foster and Plumtree — his forwards coach — focused much of their attention on the maul last year. After setting 2.0 successful mauls per game on 8.2 won lineouts in tier-one fixtures in 2019, the All Blacks set 6.2 on 14.0 lineouts in 2020 — and a number of their tries came from playing off this platform.

In the third Bledisloe test in Sydney, for instance, three scores were built on the back of a strong maul: Karl Tu’inukuafe (on second phase) and Richie Mo’unga (on first phase) both took advantage of space on the blindside after pushes infield, before Dane Coles scored directly from the boot to round out a dominant first-half display.

Then, when they did attack from ball off the top, Caleb Clarke’s presence on the left wing was a valuable asset. His size and power in contact allowed the team to carry a more lightweight midfield without forgoing a heavy first-phase ball-carrier.

Clarke, of course, has decided to pursue an Olympic medal in Tokyo, and won’t form part of the All Blacks’ squad for the first portion of their season.

While Leicester Fainga’anuku performed superbly in a similar role from set-piece platforms for the Crusaders this year, the selectors have chosen not to include him as a like-for-like replacement — a decision which will likely leave the team slightly less capable in this facet of the game.

Their maul, however, should be just as prominent as it was last year.

In fact, one of World Rugby’s law changes for 2021 — which come into force on August 1 — might make it something they rely on even more heavily.

The introduction of the 50-22 law — which Foster recently described as “a little bit of a niggle because none of us have tried it apart from Australia” — into test rugby is ostensibly a means of creating additional space in the front line by forcing defences to hold another player in the backfield.

But it will also reward teams that kick proactively and accurately from inside their own half with invaluable lineout platforms to play off in the red zone.

In any case, unless teams drastically alter their defensive set-ups, [the 50/22 law] is a change likely to further tilt the competitive balance of test rugby even further in favour of teams that are able to dictate where on the field the game is played.

Properly harnessed, it could become a real weapon for the All Blacks’ stable of skilful kickers — particularly if they persist with Beauden Barrett and Richie Mo’unga in tandem, or use David Havili frequently in the midfield.

This law won’t be in play over the next few weeks against Tonga and Fiji, but Foster may look to alter his team’s kicking strategy in advance of its implementation so that they can hit the ground running in the Rugby Championship.

In any case, unless teams drastically alter their defensive set-ups, it is a change likely to further tilt the competitive balance of test rugby even further in favour of teams that are able to dictate where on the field the game is played.

Luckily for the All Blacks, that is a tactical direction their coaching staff appears to be moving them in already.

Running rugby will likely always be an indelible part of the team’s identity — but, if they are to return to the top of the tree in 2021, they will need to continue to focus on taking back control.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free