It’s fair to say that not everyone has been pleased with New Zealand Rugby’s introduction of a number of new law variations for the 2021 edition of Super Rugby Aotearoa.

The reasoning which underpins the captain’s referral, which allows teams to challenge refereeing decisions under certain circumstances, is sound. However, it has been in the spotlight as a consequence of a couple of poor applications of the system — most notably Paul Williams’ decision to uphold a Crusaders try following a challenge by Chiefs captain Sam Cane during the rivals’ Round 3 fixture in Christchurch.

However, the new goal-line drop-out law — which, according to NZR’s Head of High Performance Mike Anthony, was motivated by a desire to speed up the game — has had its very purpose questioned.

Speaking to Stuff last week, Blues forwards coach Tom Coventry rued the fact that a team which has a ball-carrier held up over the try line must now restart play by receiving a drop-out around the halfway line, where previously they would have been awarded a scrum.

“I like to see teams rewarded for constant attacking pressure,” he said, “and getting held up over the try line and getting a scrum off the back of that is good for the game. I’m a purist, I love the scrummaging battle — the battle within the battle is part of the game.”

While Coventry’s Blues pack have still opted to use the set piece as an attacking weapon on a number of occasions already this year, across the entire competition the change has reduced the number of scrummaging battles near the try line.

According to data from Sports Analytics, through five rounds of Super Rugby Aotearoa attacking teams have completed an average of 1.8 scrums per game after an entry into their opponent’s 22.

Across the ten rounds of last season’s competition, that figure was 2.3 per game — despite the average number of 22 entries rising from 14.2 per game last year to 19.5 this year.

The law change has impacted teams’ lineout strategy too. Speaking on RugbyPass podcast the Aotearoa Rugby Pod during the pre-season, Crusaders scrum-half Bryn Hall noted that the higher cost now attached to being held up might force teams to move away from using their maul close to the try line.

The available data on this topic presents a slightly more complex picture, but Hall’s intuition looks to have been broadly correct.

While Coventry’s Blues pack have still opted to use the set piece as an attacking weapon on a number of occasions already this year, across the entire competition the change has reduced the number of scrummaging battles near the try line.

According to Sports Analytics, the average number of lineouts per game completed by attacking teams after an entry into their opponent’s 22 has risen from 6.6 in 2020 to 9.5 in 2021. The number of attacking mauls has also increased at the same rate, from 3.9 per game to 5.9.

However, according to data collected by The XV, there has been no increase at all in the number of tries scored by a player bound to an attacking maul: that figure has remained constant at 0.7 per game in both 2020 and 2021.

This lower scoring rate indicates that teams may be releasing the ball from mauls more quickly this year compared to last.

And this theory is further supported by the fact that, in 2021, Kiwi teams have already scored five first-phase tries after releasing the ball from a lineout maul — equalling, in only 10 games, the total number scored across the entire 2020 tournament.

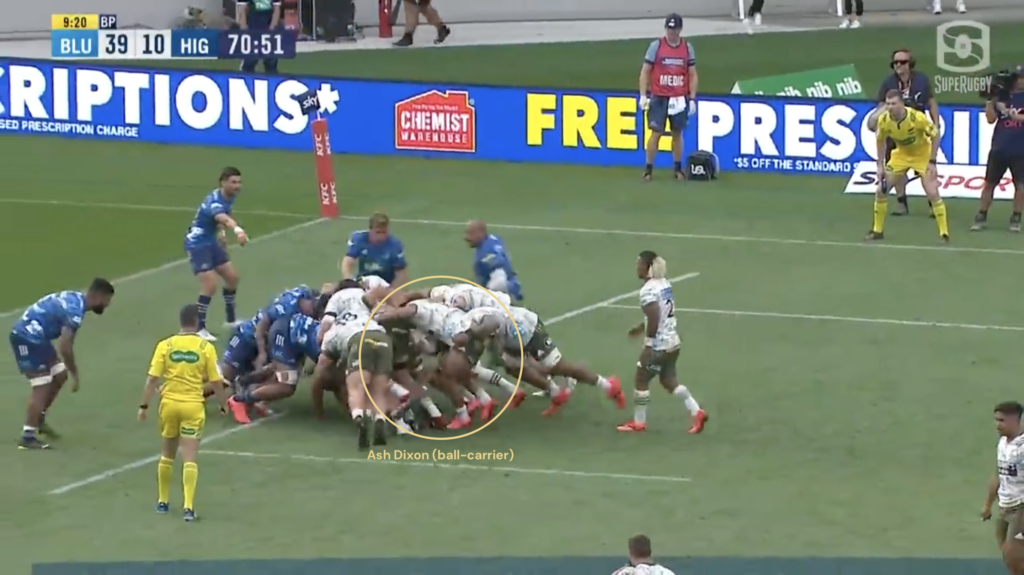

The Highlanders’ two tries at Eden Park in Round 3 are an interesting pair of scores to consider as a possible illustration of this change of strategy.

Their first try against the Blues sees the visiting pack set their maul up effectively in a long, narrow shape, with Ash Dixon holding the ball at the very back.

In this instance, the maul is able to cross the try line with considerable momentum, and Dixon can ground the ball under no pressure from the defence.

Their approach for the second was slightly different. In this case, the Blues managed to stall the Highlanders’ momentum earlier, with Dixon (again holding the ball) closer to the centre of the maul.

In that position, the Blues defenders can access the ball more easily, and as a result there is a greater risk of the hooker being held up if the maul does make it across the line.

Presented with this less favourable picture, replacement scrum-half Folau Fakatava makes a quick decision after referee Mike Fraser lets him know that the Highlanders have had their first permitted stoppage.

Rather than leaving the ball in the maul for a second shove — and risking having to traipse away empty-handed to receive a drop-out if they cannot ground the ball — Fakatava breaks to the right, and is able to fight across the line himself for five points.

On the Aotearoa Rugby Pod, Hall speculated that receiving less of a reward for being held up might also alter how teams approach their phase play beyond the 22m line.

Discussing the possibility of fewer repeated pick-and-go sequences close to the try line, he said: “It probably just opens up more opportunities to play rugby and have more manipulation around how you can get over the line. There might be a little more play with the backs being able to use it a little bit earlier and giving them more of an opportunity to have ball in hand.”

While the pick and go hasn’t yet gone extinct, there has been a clear change in how teams have approached the problem of scoring from ruck ball in the red zone this year.

It probably just opens up more opportunities to play rugby and have more manipulation around how you can get over the line.

Crusaders halfback Bryn Hall on the in-goal law changes

Specifically, it appears that teams are now more focused on forcing the defence to shift its gaze by moving the point of contact away from the ruck.

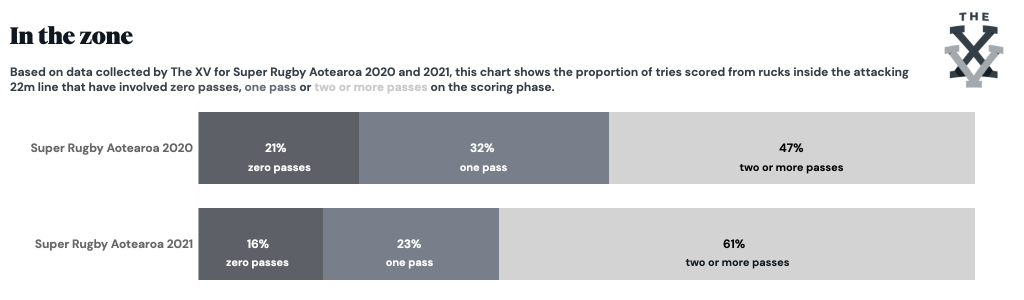

According to data collected by The XV for the 2020 season of Super Rugby Aotearoa, a majority of tries scored directly from rucks inside the 22 came either after no passes (for instance, a pick and go or a snipe around the fringes) or one pass away from the breakdown.

In 2021, however, such scores are a significant minority. To date this season, over 60% of tries from rucks inside the 22 have come on sequences which involve two or more passes.

It’s likely not coincidental that such a marked change has occurred in the same season as the introduction of a law variation that disincentivises attempting to score through a pile of large bodies — and one team has taken it further than any of the others in the competition.

So far this year, the Hurricanes have scored six tries from rucks inside the 22. Remarkably, all six have involved at least two passes on the scoring phase.

Those six scores have also seen them show off a variety of different skills and shapes. Two have involved kick-passes — Jordie Barrett to Julian Savea for Peter Umaga-Jensen to score in Round 2, and Ngani Laumape to Salesi Rayasi in Round 4 — and the most recent three have come from the inventive minds of head coach Jason Holland and assistant Tyler Bleyendaal.

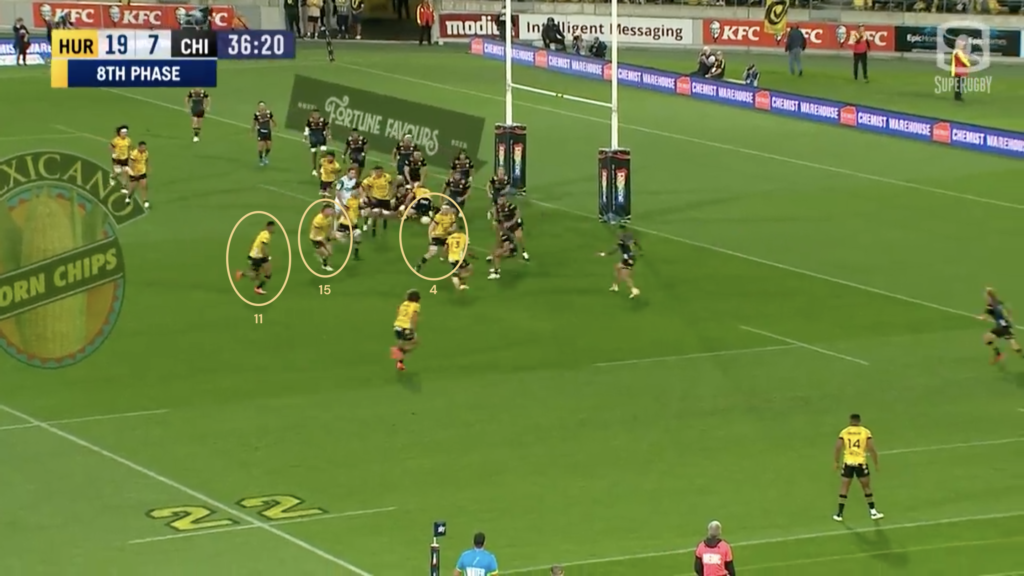

In the first half of that Round 4 fixture against the Chiefs, they set up their attack from a ruck on the 5-metre line with Jordie Barrett trailing a pod of two players in a fairly conventional shape.

But all is not what it seems. When James Blackwell (4) turns to play a screen pass, the target is not Barrett (15) but Salesi Rayasi (11), who is also hovering in the second wave of attack.

After receiving the ball directly from Blackwell, the left wing has the time to take advantage of a bad read of the play by the Chiefs’ defence and accelerate into space to score.

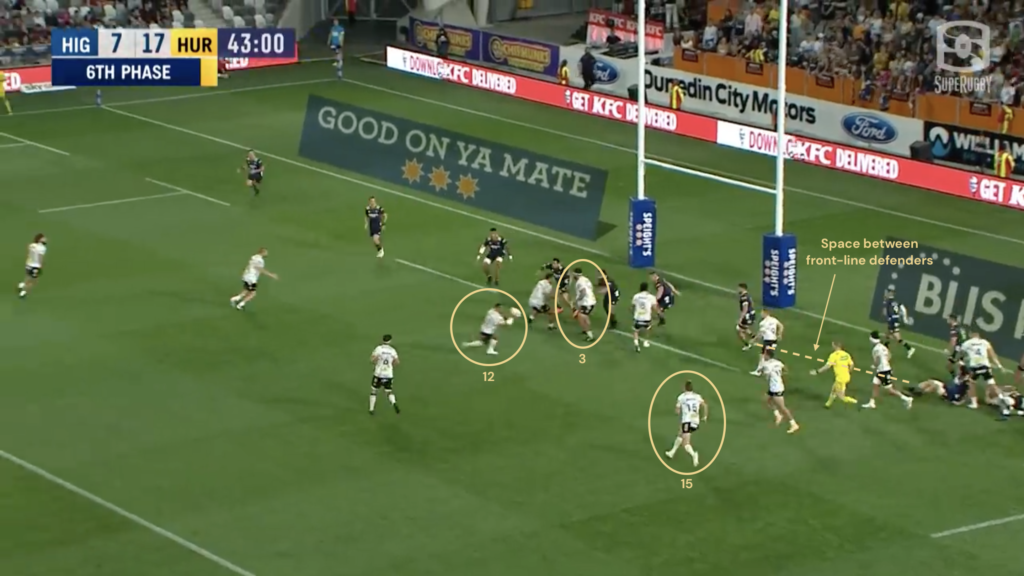

Then, in last weekend’s win in Dunedin, the Hurricanes were once again able to use the defending team’s instincts against them.

Two red-zone tries were produced from the same innovative structure: after dropping a pass from a forward in the front line to a back behind a screen, they immediately switched the direction of attack back towards the ruck.

The second of those scores perfectly illustrates the shape’s effectiveness. Tyrel Lomax (3) turns and plays the ball to Ngani Laumape (12) behind the run of another forward, before Laumape plays Barrett (15) into the same space a one-out runner might have hit.

Because of the way that the Wellington franchise has manipulated the actions of the defence — and some cute work ahead of the ball from Ardie Savea and Luke Campbell — that space is now vacant, and Barrett can crash over.

Many of the concerns raised about the new goal-line drop-out law are valid and in good faith, but examples like these make it clear that its implementation has sent attack coaches across New Zealand back to the drawing board to reconsider the best way to create scoring opportunities.

In the pre-season, it was expected that those coaches would put more of a focus on short kicking, with grubbers grounded by the defence now providing the attacking side with a more attractive restart than the 22-metre drop-out initiated under the old laws. However, this has not yet materialised: Bryn Hall’s grubber for Jack Goodhue to score against the Blues in Round 4 is the only try from a grubber kick into the in-goal area so far this season.

Nonetheless, the variation has succeeded in generating more varied and interesting approaches from attacking teams looking to keep the ball in hand close to the try line — and making those pivotal possessions in the red zone an even more entertaining spectacle for fans and viewers.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free