The Springboks defensive system, at its peak in the 2019 Rugby World Cup, was a very tough nut to crack.

When the Springboks were full strength with nearly every first choice starter available, they put forth an impressive demonstration of defensive power.

During 2018, when Rassie Erasmus first took over, it wasn’t yet at the same standard as the new coach trialed different combinations and experience was still being built. Whenever second-choice players were inserted to fill certain roles, it understandably did not operate at the same level of dominance.

Now, after nearly two years out of international action, it could be hard for the players to step back in and play at the same level immediately, giving the touring British and Irish Lions a chance to find more opportunities.

There are takeaways to be had from parts of that 2018 season when the Springboks were developing and honing the defence that ultimately won them the World Cup, as there will be times during the Lions series that the defence operates at a similar level.

Similarly, international teams still tried to attack the Springboks in 2019 during the World Cup with the same strategies that were visible in 2018, confirming where the greatest holes in the armour were.

Strength to Weakness

The forward pack of the Springboks is a strength, and the middle of the field is where they often pound runners into submission during defensive sets. The loose forward trio are heavily influential in this area of the game, and this led to Pieter-Steph du Toit earning World Player of the Year in 2019.

Carrying into the teeth of the Springbok pack up the middle is a tough ask, as this is where they thrive.

However, the tight five is not the most mobile, particularly the front rowers. They can be isolated following set-piece platforms to create mismatches in areas away from the middle where they dominate.

There are ways to turn their strengths into weaknesses, and we saw opposition teams do this in 2018 from short lineout packages.

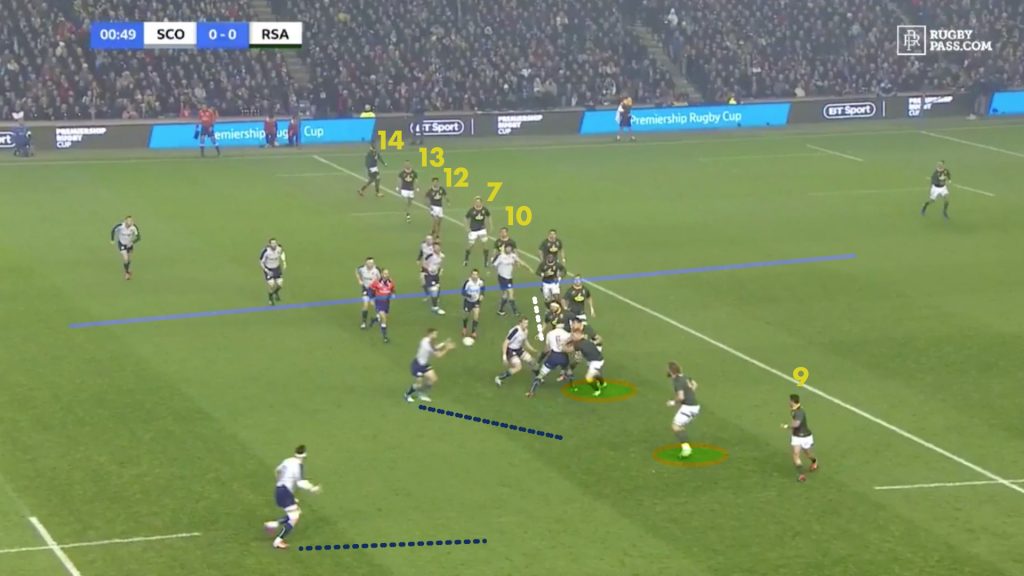

In 2018, Scotland successfully mitigated the Springboks back row by taking them out of play and isolating the tight five on the short side following a set-piece launch from a four man lineout.

Using an 11-pattern, playing one phase one way and then one phase directly back, they switched play back towards the Springboks big men in order to target them.

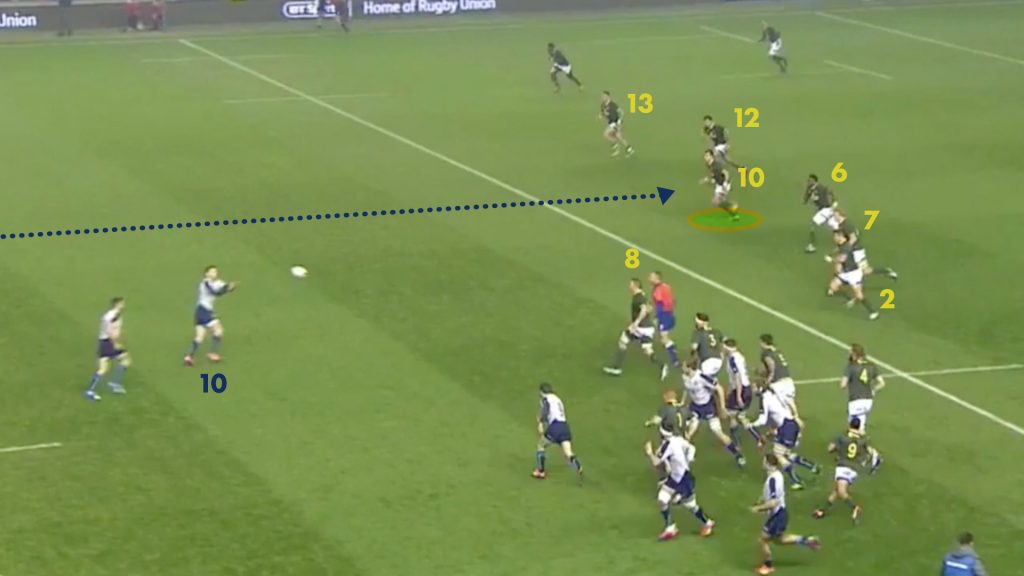

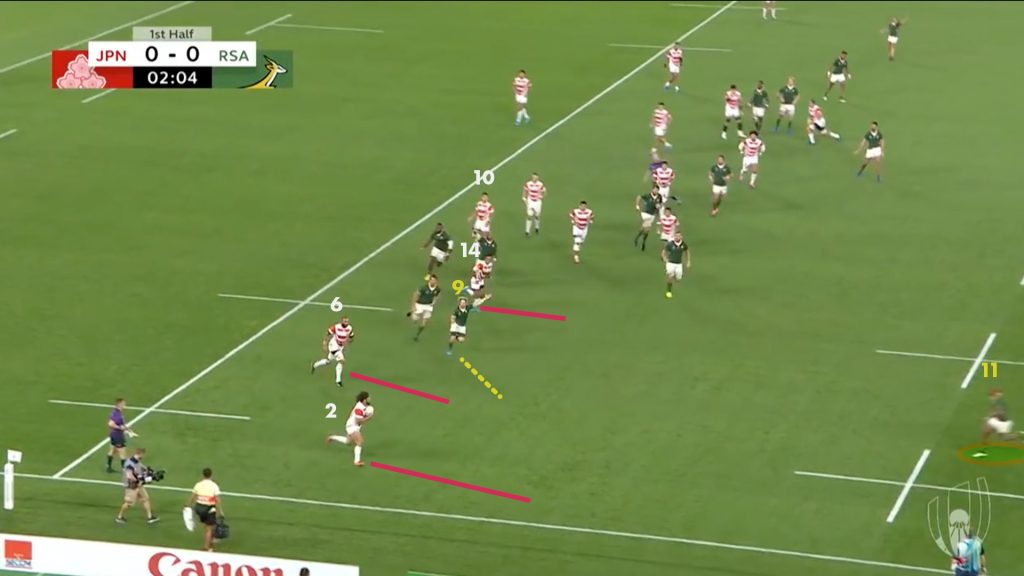

Using the short line out variation forces two of the Springboks backrow, Siya Kolisi (6) and Pieter Steph du Toit (7), into the defensive line where they align to protect Pollard’s inside channel, while Malcolm Marx (2) switched with halfback Embroise Papier (9) at the front of the lineout.

Papier plays the ‘adjusting defender’ role on the edge in the Springboks system, floating between the backfield and backside edge as required. The halfback is always required to play this role in their defence.

It is a role expertly performed by Faf de Klerk to a level so high that really no other player can match his efforts. With Papier on the field instead of de Klerk, Scotland had considerably more breathing room.

Scotland play to the midfield, outside the Springbok back row, using a wider loose forward runner to target flyhalf Handre Pollard (10) and force him to make the tackle on the outside shoulder, playing away from the likes of Kolisi and du Toit.

Although the Springboks back row are not required to tackle, as a capable fetching unit they are in position to strike on a tackled ball carrier.

It is key to protect the runner and Scotland did so by perhaps overcommitting to the ruck with extra numbers in order to make sure they secured possession.

The Springboks back row was not interested in competing and proceeded to fan out around the ruck.

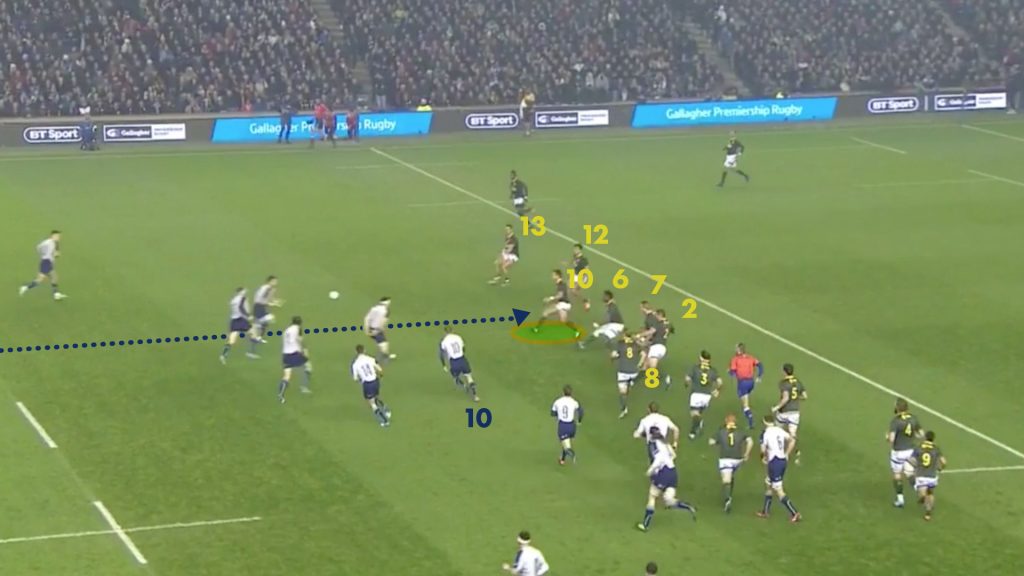

What Scotland have successfully done after the first phase is split the Springboks backs in the front line 4-1 and isolate most of the tight five forwards on a very large ‘back side’ towards the original line out.

Splitting the field in half we can see most of the Springboks backs are on the far side, and the only back on the backside is halfback Papier, the last man on the edge. Four of the tight five forwards are stationed inside Papier, including both props.

Using a hook play with winger Byron McGuigan wrapping around blindside John Barclay, Scotland create a nice opportunity on the edge for McGuigan. The Springboks forwards engage into contact with Barclay and create a half-chance for the wing.

McGuigan tries to back his speed and take the gap inside lock RG Snyman and prop Kitshoff but on this occasion, he is tackled. A more accomplished ball-player like Stuart Hogg would perhaps have made more of this situation with the option to draw and pass available.

The Springboks were vulnerable with a numbers disadvantage and disconnected defenders, plus left with mismatches against faster Scottish backs.

This is where mismatches are to be had: scheming switch plays using some of the best assets at the Lions’ disposal, such as Hogg as a sweeping playmaker interlinking with speed against tight five forwards stuck on a wide blind side.

With a player like Louis Rees-Zammit outside him and perhaps a loose forward like Sam Simmonds or Jack Conan lurking on the edge, the Lions could make the Springboks tight five work extremely hard to contain them.

These 11-pattern schemes take players like Pieter-Steph du Toit out of the game on defence, who will begin to feel like he is running all day but not making any tackles. Du Toit is visible above standing on the far side away from the action.

The difference maker for the Springboks is Faf de Klerk, who brings much more pressure than Papier in the ‘adjusting defender’ role and often saves his side from disadvantaged positions.

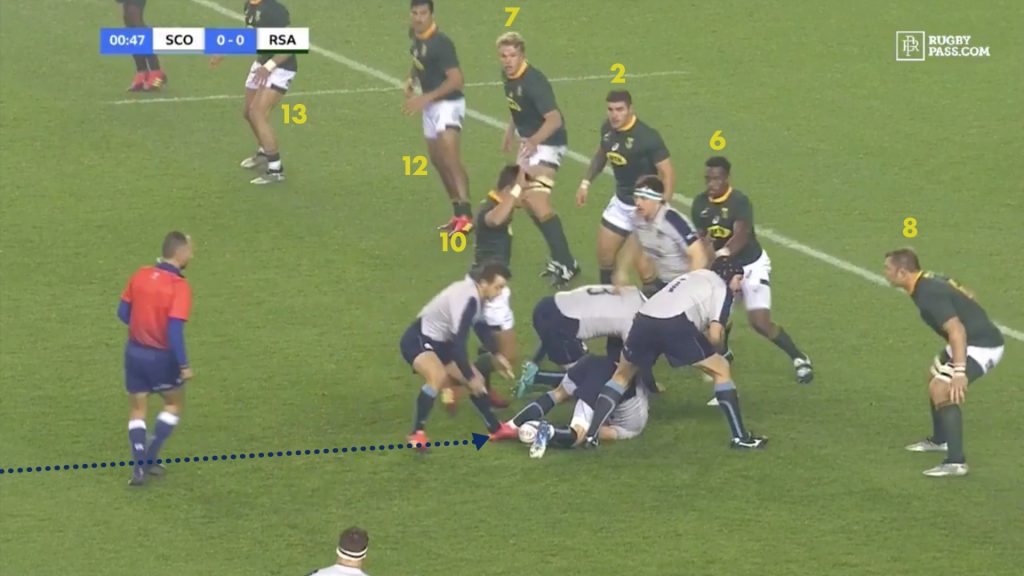

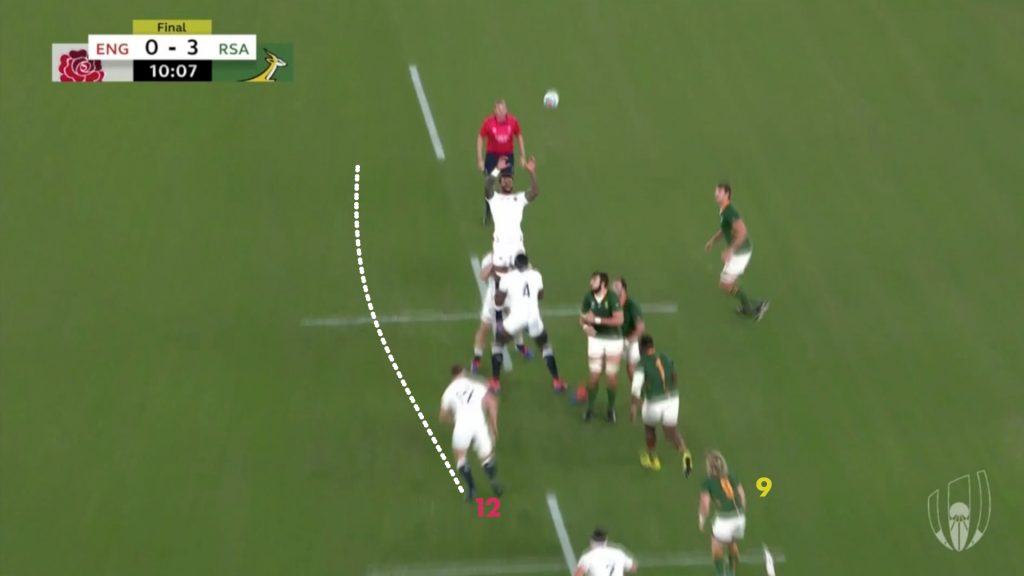

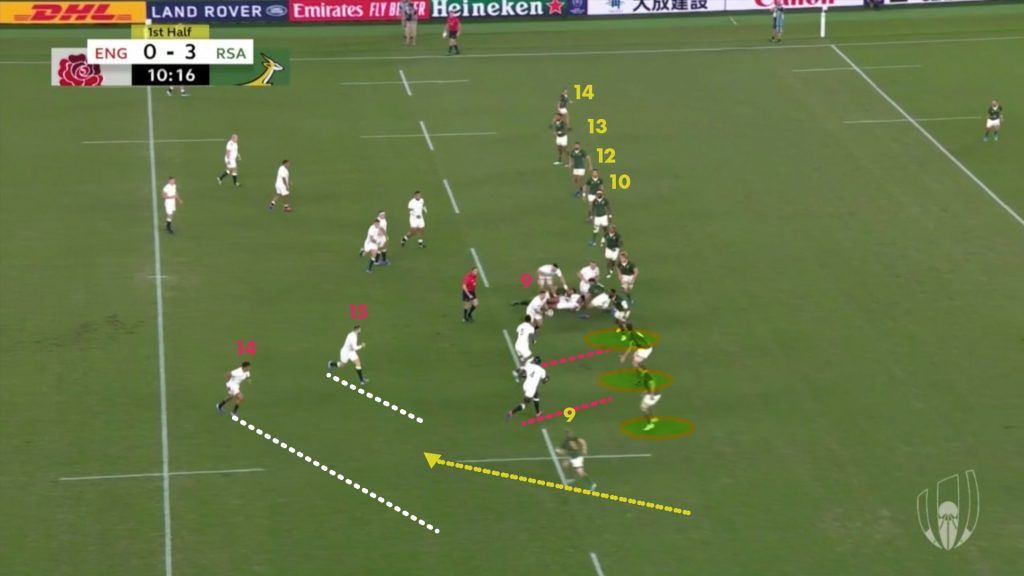

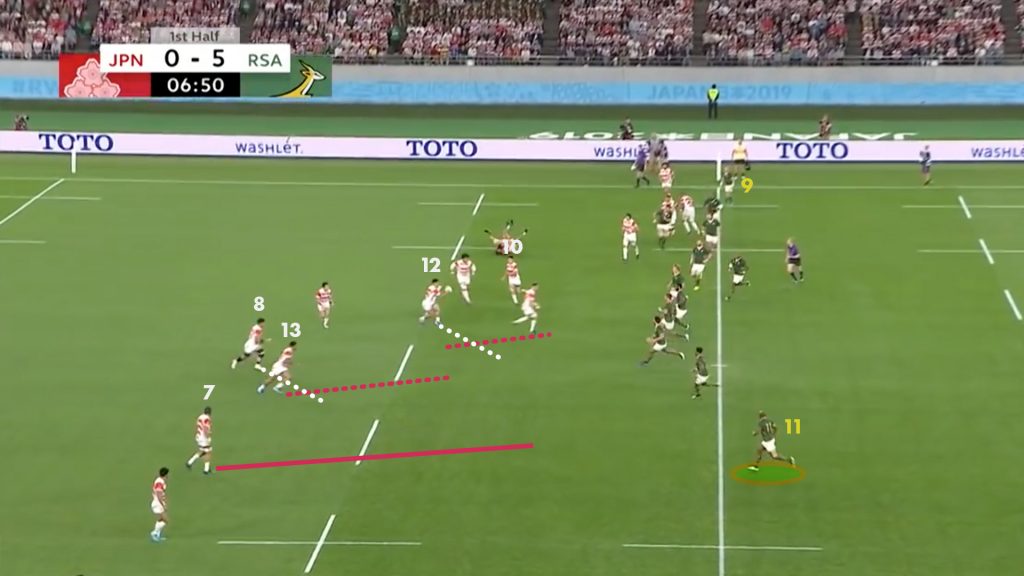

England tried to attack the same area of the field as Scotland early in the World Cup final, again using a four man lineout to get the isolated back side look they were after.

England avoids the Springboks back row contingent just like Scotland, this time by running Manu Tuilagi (13) underneath Ben Youngs (9) back into the Springboks tight five instead of playing wide outside Handre Pollard.

By forcing Lood de Jager (5) and Frans Malherbe (3) to make the first-up tackle on Tuilagi, England has an even more advantageous set-up on the backside for the switch play compared with Scotland.

Just two South African tight five forwards reset the defensive line on that side while Duane Vermeulen (8) recognises he needs to be there to help with the frontline Springboks backs again in a 4-1 split.

England have a great setup for the quick switch back but the ability of de Klerk to influence the play, disrupts and ultimately repels the attack.

De Klerk (9) diagnoses the potential danger quickly and rushes up out of the line to pressure England.

By flying into the passing lane, De Klerk forces a panicked pass by Youngs that sails over Anthony Watson’s (14) head into touch. The Springboks force a turnover and avoid having the line breached out wide.

De Klerk is the roadblock to success on these plays but the opportunity is still there despite his immense talent in defence.

He is able to shut down plays when the odds are against him but no one can beat the odds every time over enough simulations.

His tendency to rush completely out of the line can be exploited.

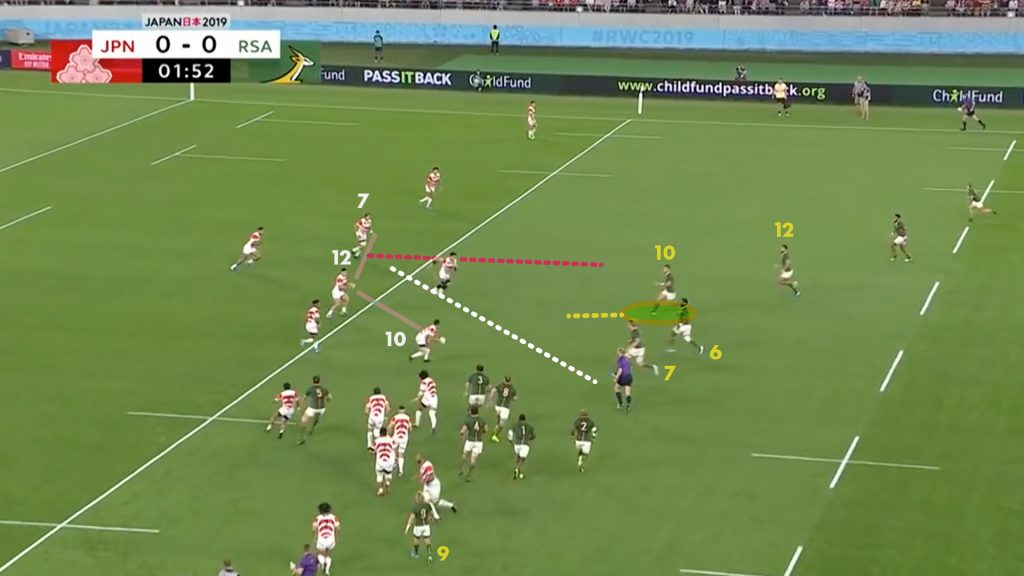

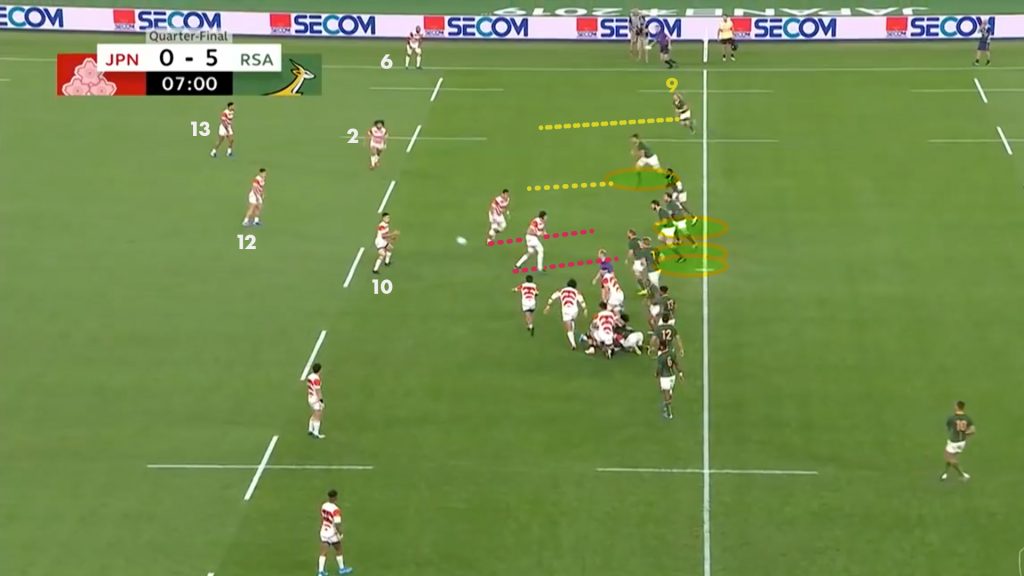

Japan had this in mind also in the World Cup quarterfinal, using the same type of switch pattern on their first two launch plays of the game.

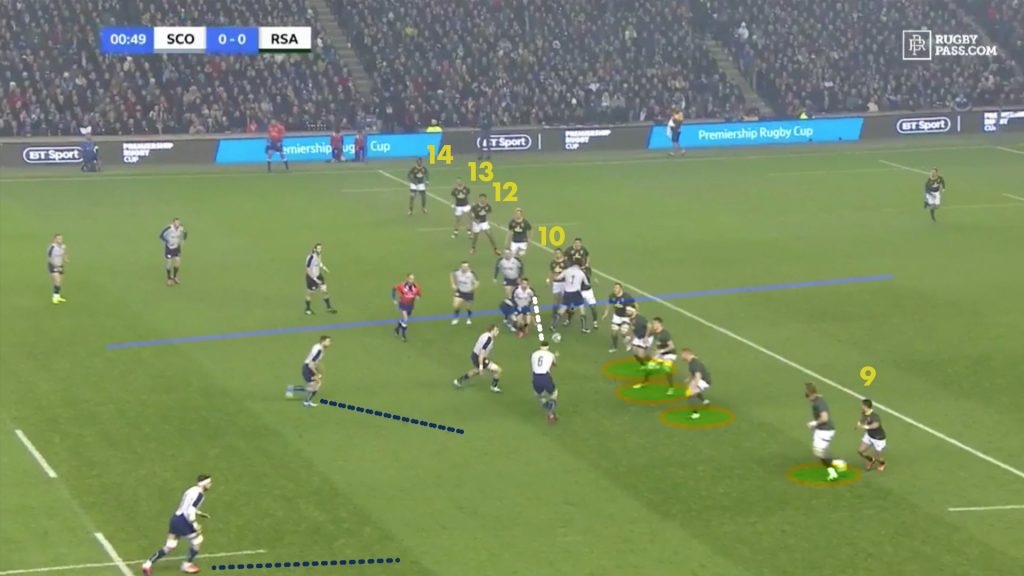

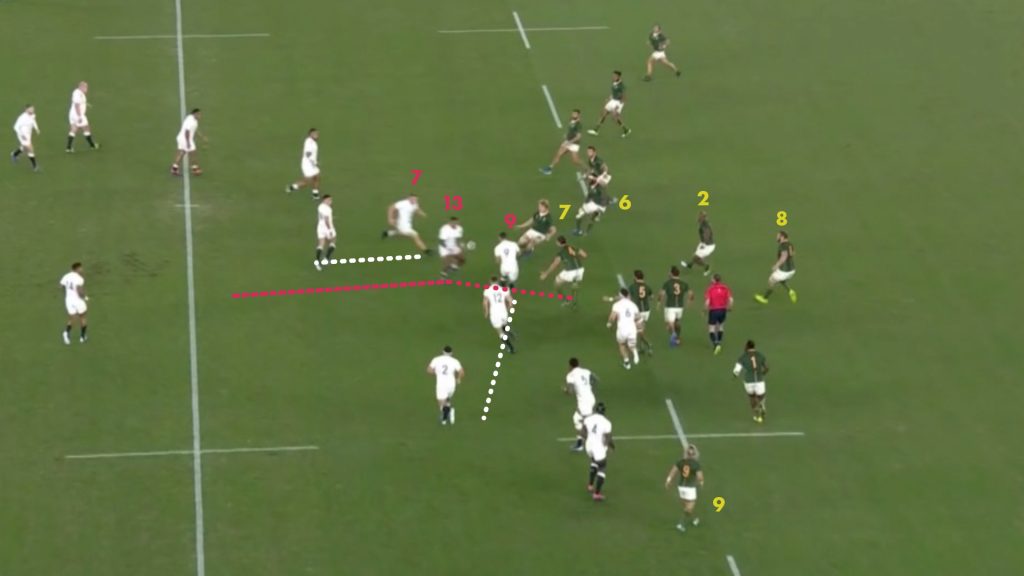

Again a short lineout is used, a five man package, to take the loose forwards out of the picture and keep the tight five close by.

Japan uses a screen runner to draw the interest of Pollard inside, before going through the hands of their 10 and 12 out the back to hit openside flanker Pieter Labuschagne (7) to crash into the Springboks 10-12 channel.

Hitting this channel works again to to set-up a very large back side. The picture they get is great, with de Klerk (9) outnumbered on the edge and only supported inside by big tight five forwards.

Japan plays Yu Tamura (10) out the back of a traditional three-man pod and have a chance to release out wide and break downfield.

De Klerk performs his usual rush to try to jump the passing lane, and Yu Tamura (10) decides to float a long ball over the top to the free man in space, hooker Shota Horie (2).

Japan has the play and Tamura makes the right read but unfortunately for Japan, Tamura’s pass is called forward and they concede possession which the Springboks then score the first try from.

What could have been a great break from Japan ends with conceding seven points through poor execution after getting the picture they wanted.

Now imagine Shota Horie is Louis Rees-Zammit, Yu Tamura is Finn Russell and Michael Leitch is Sam Simmonds and you have far more on your hands to deal with.

No disrespect to Japan’s players but the Lions will have more speed at their disposal out wide, and Russell has proven to be perhaps the best player in the world at throwing a long cutout pass.

This play is the perfect set-up to use Finn Russell’s skills to cause havoc on the Springboks backside defence, should he start at 10 for the Lions.

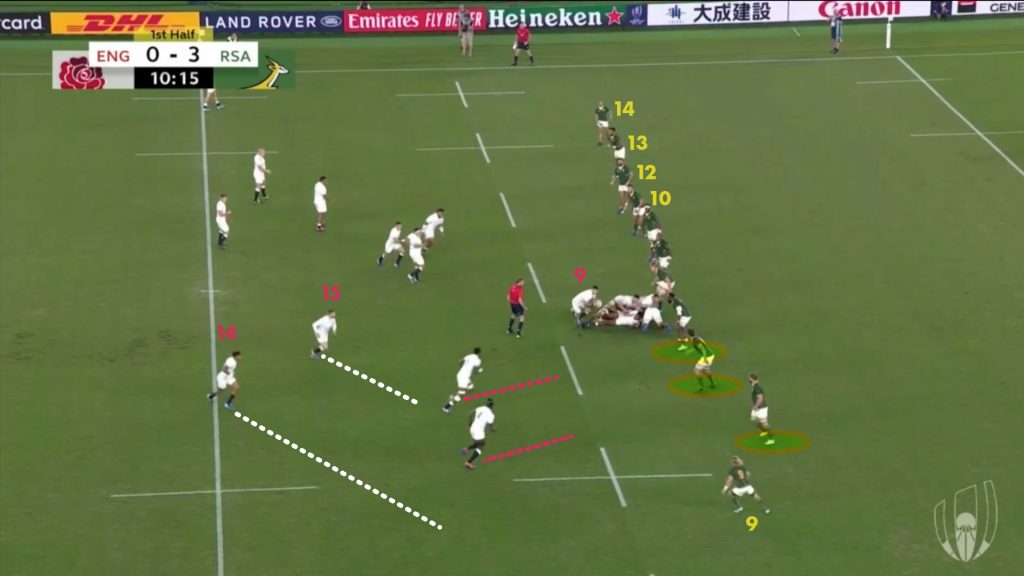

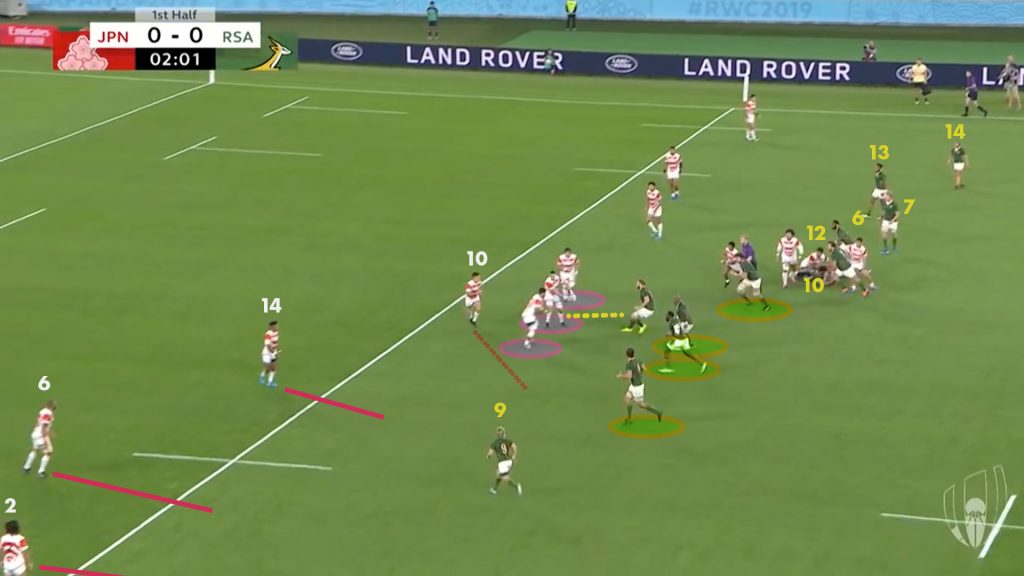

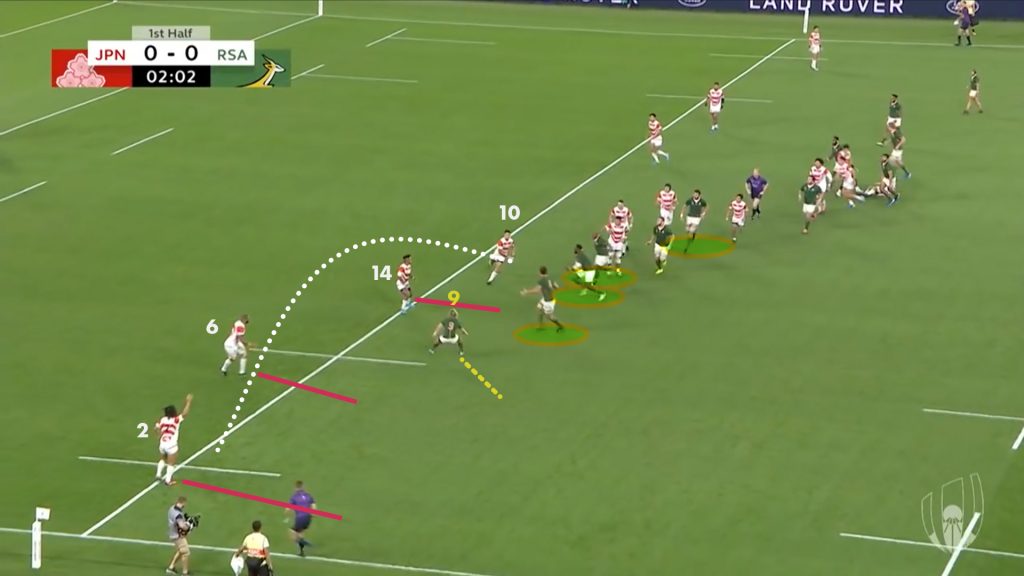

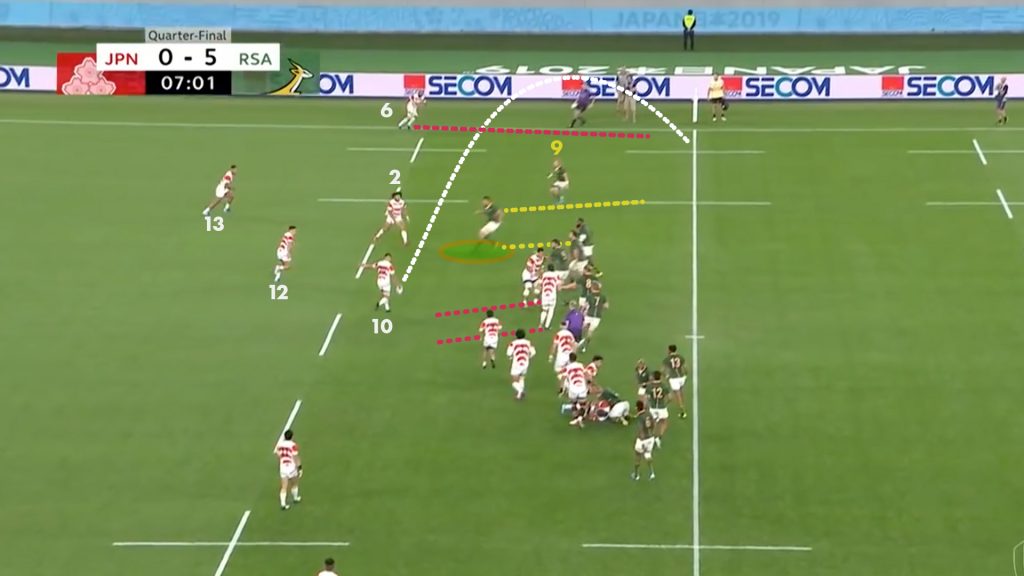

On Japan’s very next attacking lineout, they tried to get a similar setup but this time went even wider, running a double screen play to send flanker Labuschagne (7) into centre Lukhanyo Am and winger Makazole Mapimpi’s (11) channel on the far perimeter.

The wide ruck sets up another large backside for the Springbok defence, and Japan again use Tamura (10) to attack the space in behind de Klerk – this time it’s a planned cross-field kick for Michael Leitch (6) hanging out on the sideline.

A low bounce stumps Leitch and the ball ends up in touch but again, the play was correct, only a slight execution error foiled the plan.

Faf de Klerk is an incredible player, but on these two occasions it was a slice of luck that saved the Springboks, not the defensive system.

Had Leitch made an impressive grab, Japan likely would have pressured the Springboks but would not have made any more of the chance due to a lack of support runners around him.

If a team is to strike from these type of plays, the support has to be screaming up on the inside in numbers.

If you work hard to create line breaks against the Springboks, you don’t want to waste them with poor support play.

This aspect will be vital for the Lions if they are to make something of the series, and they have selected a squad with plenty of speed to make sure fast break opportunities don’t go to waste.

It is critical for the Lions to strike fast and early and put the South Africans in a hole which they cannot climb out of. At altitude it will be tougher and tougher as the games go on so early strikes are necessary.

The reality for the Springboks is they are not built to chase points. They are built to defend and kick threes. If they fall behind by two tries, the game is practically over.

The All Blacks struck twice within a 10-minute period during the first half of the World Cup pool contest to build a 17-3 lead and that was all that was needed.

If the Lions smell this same weakness in the defensive system, they should pursue it relentlessly in search of a couple of early fatal blows.

In Japan’s case in their quarterfinal, they varied away from this plan after their first two launch plays and instead began attacking other areas of the field from set-piece with limited success.

With the fast pace game Japan played, testing the Springboks tight five back on the short side a few times later in the game when they were further fatigued, before the second tight five entered from the bench, could have been wise.

We have seen a number of teams pursue this opportunity when playing the Springboks from the line out, confirming this tactic as one of the best ways to attack their defensive system.

Everyone has seen it. Many have tried it. None have executed to the level needed. That is the challenge for the Lions.

The Lions have the talent to execute, and playing the backside off short lineouts should be just one of the strategies they employ in South Africa.

More stories from Ben Smith

If you’ve enjoyed this article, please share it with friends or on social media. We rely solely on new subscribers to fund high-quality journalism and appreciate you sharing this so we can continue to grow, produce more quality content and support our writers.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free