Analysis: The blueprint Gatland provided that shows how to expose the Springboks defence

“There is no innovation and creativity without failure. Period” – Brene Brown

“No matter how organised a defence is, there will always be space on a rugby field”. Any young player, would have at some point, heard these words from their coach, from U12’s through to 1st XV level. Identifying space, and attacking it at a moment’s notice, is what the entire game of rugby is about.

However, doing this often requires a wide variety of skill sets that are so often outside of the box.

Defences nowadays are geared towards the modern game, designed to work against structure and patterns in play, whereas fluidity and the freedom to move away from this, maybe harder to combat.

This gives rise to the term that with the increasing efficacy of defences, that playing it safe, maybe the worst thing you can do.

The South African defence is designed to eliminate the likely options that structure provides. Whereas a change in thinking and a willingness to embrace the risky option may yield better results against this defence.

Set-Piece

Of all teams to play Rassie Erasmus’ South Africa, the team that showed an unusually wise tactical acuity of them was Wales.

New Zealand beat them, but when South Africa’s defence was on point and full-on in its intensity, the team that outsmarted them using established sequences off set-piece was Wales.

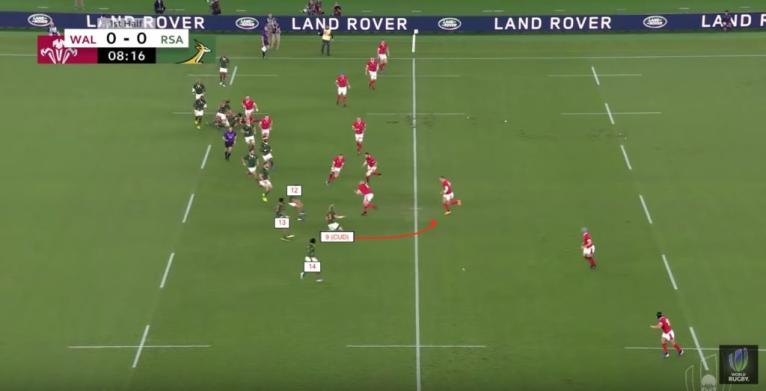

They were able to get on the outside using set three-phase sequence plays that allowed them the ability to put the ‘catch-up defender’ (CUD) in two minds, achieved, with the miss-pass or commonly known as M1.

Wales run George North on a short pass to target the No. 9, followed by a forward pod up the guts into the midfield.

This forward pod is very important to the success of this move. It is designed to hold the fold-over of the Bok forwards and result in Welsh backs exclusively targeting Springbok backs.

This is where the genius of this play comes in. Having established a backline against a backline, Wales throw a miss pass from the first receiver, directly to the third receiver, executed by Gareth Anscombe to Liam Williams above.

This circumvents the South African defence’s standard operating procedure of cutting off the second receiver, who was Jonathan Davies.

Because the last defender, Cheslin Kolbe above, has to remain in line with the CUD until the pass is given from the second receiver, he has too much ground to make up.

This allows the third receiver, Liam Williams, time to get the pass away to Josh Adams, who makes a significant break.

Going forward the third receiver must remain at depth, and the pass given early so the CUD can’t block the passing lane.

It has to be a pass given in front of the second receiver, so he can act as the bait for the CUD role to tackle him.

This is not the only occasion that this three-phase framework worked for Wales. The ‘first receiver M1’ play is key to beating this edge defence, as it allows the third receiver time and space to pass to the wing and get around the defence.

Wales were keen to set into this pattern a year later, in one of their most important ever games.

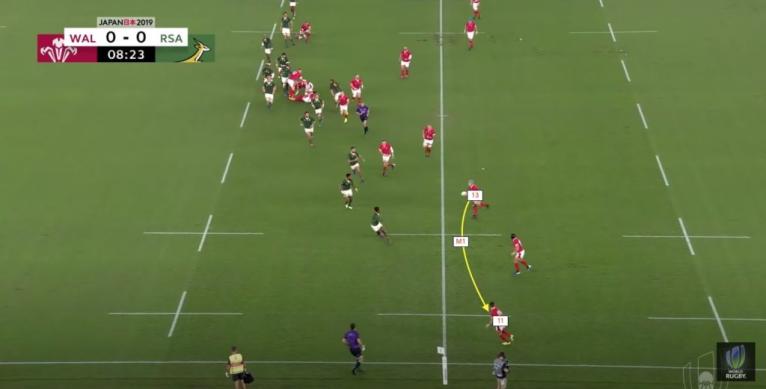

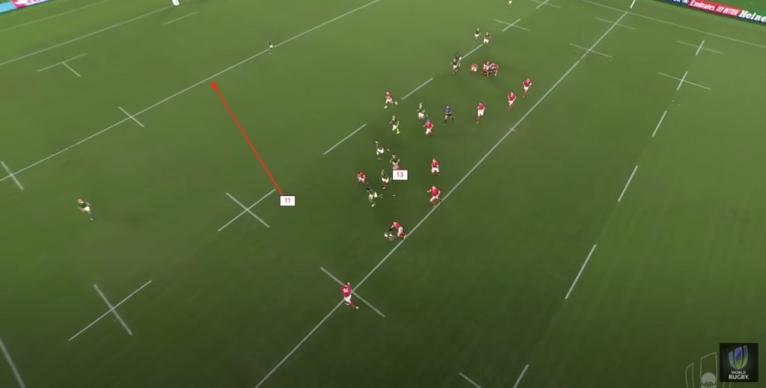

Here, we see Wales packing down for a scrum near just inside the 15m line. Due to the benefits, Gareth Davies picks from the base and runs a blindside scoot, releasing George North.

Significant ground is made, and they start their three-phase movement. The 3-pod carries as above as the first phase, the objective being to generate quick ball.

In the second phase, we see the CUD move forward to cut off the expected second receiver option, but instead, Dan Biggar plays the key move to isolate the backline.

Biggar passes to Ken Owens, who runs an out-in line to target the ‘forward’ portion, restricting the fold over and isolating the backline for the third phase.

This is crucial. The 10/12, as a general rule, will only move over to the blind during the first three phases off lineout in particular, if the ball goes past them, or hits them.

If the attack keeps it tight and only targets the folding forwards, the backs won’t switch which means by the third phase, they’re strictly targeting the backline.

This means they’ve thinned the line, prevented the Boks from numbering up and created the overlap, with a single back in the scrumhalf on the blindside, whom we should keep a note of for later.

The inside angle of Owens has stopped the ‘fold over’ of the forwards, with most of them in the ruck, isolating the backline for the third phase attack and creating the overlap where Lukhanyo Am is seen calling for help.

Because of this, the Springbok backs set into a drift, whilst maintaining their pressure on the second receiver. It must be noted, that whilst a very good player, Sbu Nkosi (14) was targeted by Wales, as he is more likely to be indecisive in this system than his replacement; Cheslin Kolbe.

As we will show later, Wales’ second receiver was given time and space to pass, that they may not have had with Kolbe. This is one reason Kolbe started the final.

Because of the drift, Jonathan Davies as second receiver has the time to make the M1 pass, putting Adams into space, and gaining considerable ground.

England made use of the 10/12 reload dynamic themselves in the Rugby World Cup final.

Off the first phase, they use Jonny May to target Faf de Klerk on the scissors.

Then run two phases off No. 9 to the right, making sure to target only forwards and leaving Pollard and de Allende alone.

This ensures the ‘1-set’ of backs is maintained on the blind, with the ‘4-set’ to the open.

England attempt to exploit this by switching play but were shut down by de Klerk. The ‘M1’ pass is not used by England squandering the opportunity.

If England was able to ghost Elliot Daly into support May, this is a run-in try.

Exploiting the scrumhalf

The change that could prove fruitful against the Springboks is for a winger to come into the midfield channel off the third receiver, where a lock switches with them on the wing.

This is the first example, of where structural innovation and particular skill sets could prove useful, and it makes use of the scrum-half position off lineout and scrums within the 15m line outside of the 22.

Within the 22, Malcolm Marx is assigned at the front of the lineout, to prevent any trick plays involving the hooker and to assist in the maul.

In any other position on the pitch, the scrumhalf stands at the front of the lineout, a staple of Jacques Nienaber’s system.

But first, it requires getting outside of the ‘catch-up’ within the first three phases. This is required to commit the Bok back-three.

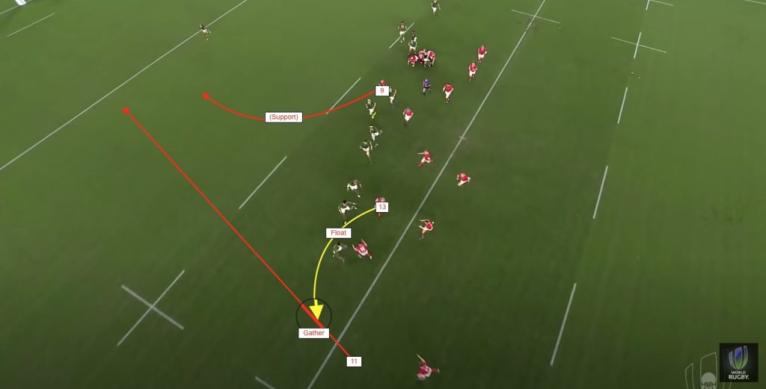

As shown below, Wales have played a two-phase sequence from the right touchline, specifically targeting Nkosi’s indecision as the CUD. In doing so, they get around the CUD, drawing in both wingers and fullback.

This position sets up the cross-kick option back towards where the lineout originated, where the No. 9 is isolated after defending at the front.

Whilst a 3-set out wide, the result shows why the most athletic, tallest lock should be opposite the No. 9. The backfield doesn’t have time to move over, hence the immediate cross-field kick is the right option.

De Klerk and Herschel Jantjjes are beasts in the tackle but can’t out-leap a 6’5 plus lock.

This option takes away the initiative the Boks want and puts the tallest man, very skilled at fielding balls from restarts, in a mismatch any scrumhalf wouldn’t want.

We saw the break earlier, with an exquisite M1 pass made from the first to third receiver by Wales.

On this occasion below, Pollard and Damian de Allende did not reload on the blindside with the No. 9 as the carriers never hit or passed them on second phase.

This left the scrumhalf alone and Kriel having to urgently fulfil the ADJ role.

The result is worse, with the backfield cover not present and the No. 9 even more isolated.

If a team can employ the ‘three-phase’ framework and target the forwards on first and second phase, an ‘All Blacks special’ in the low hanging cross-field kick could play dividends with the No. 9 isolated against a lock.

The mismatch between the tall man and the short one has been used before, for some players in their most important ever game.

Rather than sticking to the structure on the fourth phase, doing the expected and sending the ‘3-pod’ in, teams can identify and create real mismatches, if they have the daring to do it.

Going forward, teams could look to use this as an alternative to targeting the scrumhalf.

South African scrumhalves are machines in the tackle. Hence, they need to be targeted a smarter way.

“Lil” Floater

The outcome of success in the floated pass, depends on two inputs, the first is the delivery of the pass, and the actions of the receiver.

A floated pass can allow a lot of outcomes. Done incorrectly it can result in an intercept. Done well, it can result in a massive gain.

The problem is that many receivers (often the winger) take the ball while static, allowing the incredible work rate and natural agility of the Springbok outside backs to catch him.

If a player can run onto it, though, they may be able to get around this drift before it catches up.

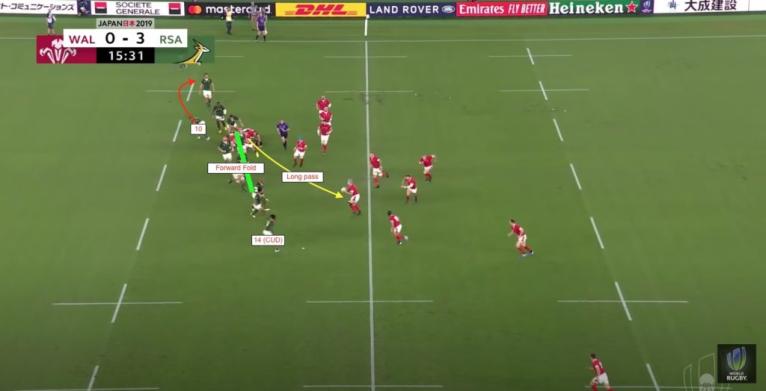

Again, we look at Wales. In contrast to their three-phase framework, they were able to use a two-phase framework designed to target Nkosi in defence.

Wales send Parkes up the No. 10 channel, automatically setting in stone the forwards fold and Pollard/De Allende’s reload to the short side.

The long pass is given to Jonathan Davies, which skips the forwards and pits the Welsh backline against the “2-set” rather than “4” of the South African edge, forcing Nkosi to make the CUD decision, their objective.

This allows the Welsh attack to get on the outside.

While effective, the time taken for the link passing and depth means the Bok defence has the time to close down the outside backs and prevent any try-scoring opportunity.

An alternative that may work is the floated pass, with the winger taking it on the run

International rugby is a game of fine margins. If Davies is able to “double-pump”, to bring Nkosi up on Biggar but instead execute the floated pass, it would lead to the winger accelerating onto the ball.

The No. 9 can operate as support on the inside, and the No. 13 can operate on the outside.

The winger has to run onto the ball for this, but this would circumvent the link passing and allow him to catch at a much flatter alignment, allowing him the time and space to get around the inside drift of the Boks and engage the backfield.

Similar dynamics have been seen before. In 2003, the willingness to do this existed, whereas current adherences to pattern can quell these moments of endeavour when they are exactly what defensive patterns aren’t designed to contain.

This dynamic will be further explored in the next article in the series.

Doing this requires a new way of thinking and the openness to embrace skill sets that have in some ways been lost. It’s not easy to do, but there is no easy way to beat a team like South Africa. Embracing new ideas could be the way.

Comments on RugbyPass

Sabbaticals have helped keep NZ’s very best talent in the country on long term deals - this fact has been left out of this article. Much like the articles calling to allow overseas players to be selected, yet can only name one player currently not signed to NZR who would be selected for the ABs. And in the entire history of NZ players leaving to play overseas, literally only 4 or 5 have left in their prime as current ABs. (Piatau, Evans, Hayman, Mo’unga,?) Yes Carter got an injury while playing in France 16 years ago, but he also got a tournament ending injury at the 2011 World Cup while taking mid-week practice kicks at goal. Maybe Jordie gets a season-ending injury while playing in Ireland, maybe he gets one next week against the Brumbies. NZR have many shortcomings, but keeping the very best players in the country and/or available for ABs selection is not one of them. Likewise for workload management - players missing 2 games out of 14 is hardly a big deal in the grand scheme of things. Again let’s use some facts - did it stop the Crusaders winning SR so many times consecutively when during any given week they would be missing 2 of their best players? The whole idea of the sabbatical is to reward your best players who are willing to sign very long term deals with some time to do whatever they want. They are not handed out willy-nilly, and at nowhere near the levels that would somehow devalue Super Rugby. In this particular example JB is locked in with NZR for what will probably (hopefully) be the best years of his career, hard to imagine him not sticking around for a couple more after for a Lions tour and one more world cup. He has the potential to become the most capped AB of all time. A much better outcome than him leaving NZ for a minimum of 3 years at the age of 27, unlikely to ever play for the ABs again, which would be the likely alternative.

1 Go to commentsJake White talks more sense than anything I've read in the last 5 years. Hope someone's listening.

9 Go to commentsThe Springboks tried going down the road of only picking home-based players and it was an unmitigated disaster in 2016 and 2017. Picking overseas-based players has been one of the main reason the Boks have done so well since 2018, not only because of the quality Rassie could call on, but because of the knowledge and experience those players brought into camp from England, France and Japan. With some of the big names playing abroad it also gave younger players in SA the chance to break through at franchise level. Would we have seen the emergence of a Ruan Nortje if RG and Lood were still at the Bulls? Not so sure. I understand why Jake would want to block players leaving since his job depends on good results but it’s an approach that would take Bok rugby back to the bad old days and no South African wants to see that.

9 Go to commentsExeter were thumped by 38 points. And they only had to hop on a train.

36 Go to commentsI am De Groot.

1 Go to commentsHad hoped you might write an article on this game, Nick. It’s a good one. Things have not gone as smoothly for ROG since beating Leinster last year at the Aviva in the CC final. LAR had the Top 14 Final won till Raymond Rhule missed a simple tackle on the excellent Ntamack, and Toulouse reaped the rewards of just staying in the fight till the death. Then the disruption of the RWC this season. LAR have not handled that well, but they were not alone, and we saw Pau heading the Top 14 table at one stage early season. I would think one of the reasons for the poor showing would have to be that the younger players coming through, and the more mature amongst the group outside the top 25/30, are not as strong as would be hoped for. I note that Romain Sazy retired at the end of last season. He had been with LAR since 2010, and was thus one of their foundation players when they were promoted to Top 14. Records show he ended up with 336 games played with LAR. That is some experience, some rock in the team. He has been replaced for the most part by Ultan Dillane. At 30, Dillane is not young, but given the chances, he may be a fair enough replacement for Sazy. But that won’be for more than a few years. I honestly know little of the pathways into the LAR setup from within France. I did read somewhere a couple of years ago that on the way up to Top 14, the club very successfully picked up players from the academies of other French teams who were not offered places by those teams. These guys were often great signings…can’t find the article right now, so can’t name any….but the Tadgh Beirne type players. So all in all, it will be interesting to see where the replacements for all the older players come from. Only Lleyd’s and Rhule from SA currently, both backs. So maybe a few SA forwards ?? By contrast, Leinster have a pretty clear line of good players coming through in the majority of positions. Props maybe a weak spot ? And they are very fleet footed and shrewd in appointing very good coaches. Or maybe it is also true that very good coaches do very well in the Leinster setup. So, Nick, I would fully concurr that “On the evidence of Saturday’s semi-final between the two clubs, the rebuild in the Bay of Biscay is going to take longer than it is on the east coast of Ireland”

11 Go to commentsWhat was the excuse for the other knockout blowouts then? Does the result not prove the Saints were just so much better? Wise call to put your eggs in one basket when you’ve got 2 comps simultaneously finishing.

36 Go to commentsReally hope Kuruvoli and his partner rock the Canes.

1 Go to commentsI wonder what impact Samson has had on their attack, as the team seems less prone to trundle it up the middle, take the tackle and then trundle it up again. I lost faith in the coach last year as the Rebelss looked like a 2nd/3rd rate South African team. I also disliked Gordon standing back, often ignored as the forward battle went on and on. Maybe its our Aussie way of not getting off our A***’s until the enemy is at the gate.

86 Go to commentsThanks for the write up. Great to see the Rebs winning, I am a little interested in how they will go against the remaining kiwi teams, I think they’ve only played Hurricanes and Highlanders but how great to see these players performing!! I also see Parling has a job beyond June 30! A good move by RA? Also how do you fix the Rebels previously scratchy defence?

86 Go to commentsbe smart - go black

13 Go to commentsNext week the Crusaders hopefully have Scott Barrett back. Will be great to have the captain back. Hopefully he will be the All Black captain as well.

12 Go to commentsExciting place to be for the young fella. I expected he was French Polynesian when I saw him included in the France 6N squad (after seeing him in NZs), and therefor be strong grounds we might loose him to rugby down here. Good, in that he is good enough to warrant such a profile, and from a journalism’s fan interaction aspect, to finally get a back ground story on the fella. Hope he has settled into NZ OK and that at least one rugby country will fit with him to help his development, which, if so, he should surely continue for a few years, and then that he can experience France to it’s fullest with a bit more maturity and less reliance on family than you would have at his current age. A good 3 or 4 years before he would be ready for International duty if he wanted to wait. Of course he already sounds good enough to accept a call up, and to cap himself, in the more immediate future (he’d have to be very very good in the case of the ABs), and he’ll get a great taste of that being with the Canes who have a bunch who are just a few years further into their career and looking likely Internationals themselves.

13 Go to commentsI remember towards the end of the original broadcasting deal for Super rugby with Newscorp that there was talk about the competition expanding to improve negotiations for more money - more content, more cash. Professional rugby was still in its infancy then and I held an opposing view that if Super rugby was a truly valuable competition then it should attract more broadcasters to bid for the rights, thereby increasing the value without needing to add more teams and games. Unfortunately since the game turned professional, the tension between club, talent and country has only grown further. I would argue we’re already at a point in time where the present is the future. The only international competitions that matter are 6N, RC and RWC. The inter-hemisphere tours are only developmental for those competitions. The games that increasingly matter more to fans, sponsors and broadcasters are between the clubs. Particularly for European fans, there are multiple competitions to follow your teams fortunes every week. SA is not Europe but competes in a single continental competition, so the travel component will always be an impediment. It was worse in the bloated days of Super rugby when teams traversed between four continents - Africa, America, Asia and Australia. The percentage of players who represent their country is less than 5% of the professional player base, so the sense of sacrifice isn’t as strong a motivation for the rest who are more focused on playing professional rugby and earning as much from their body as they can. Rugby like cricket created the conundrum it’s constantly fighting a losing battle with.

9 Go to commentsOh wow… “But as La Rochelle proved in winning in Cape Town this season, a cross-continental away assignment need not spell the end of days.” La Rochelle actually proved quite the opposite. After traveling to Cape town and back they (back-to-back and current champs) got mercilessly thumped the next week. If travel is not the reason, why else would a full-strength powerhouse like La Rochelle get dumped on their @r$e$ one week later?

36 Go to commentsYou know he can land a winning conversion after the full time siren is up. (Even if it takes two attempts.)

5 Go to commentsA very insightful article from Jake. I would love to know how South African’s feel about their move to Europe. Do you prefer playing in Europe or want to go back to Super Rugby?

9 Go to commentspure fire

1 Go to commentsA very well thought out summary of all the relevant complications…agree with your ”refer the Cricket Test versus 20/20 comparison”. More also definitely doesn't necessarily mean better!

9 Go to commentsMust be something when you are only 19 y.o and both NZ and France want you. Btw he wasn’t the only new caledonian in french U20 as Robin Couly also lived in Noumea until 17. Hope he’s successful wherever he chooses to play.

13 Go to comments